Dish of the Day

Just some film musings of a more succinct, spontaneous and sometimes seditious nature:

Sunday, February 18, 2024

How Quentin Tarantino’s “One of the Worst Decades in Hollywood…” Was Actually One of Its Greatest

Part 2: Where the filmmaker and I, more or less, agree, the ‘80s

(For Part 1: An Introduction, click here).

For the experienced and discerning viewer, so much cinema of the ‘80s felt “safe” or at least “safer” than a vast number of distinguished films released in the previous two decades. Motion pictures of the late ‘60s and ‘70s tested their newfound freedom with the volcanic ruination of the Production Code. It didn’t matter how unsavoury the material was, how unappealing the characters were or what tragedy might befall them.

The greater majority of films from the 80s put an end to that. An almost imperceptible line was established that we knew would not be crossed regarding character delineation, behaviour, their surrounding events and outcomes. This barrier had been shattered in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) by killing off the central person of interest rather early in the story and at her most vulnerable, presented in as gruesome a manner possible for its time. By comparison, we were always aware that no such calamity would befall the mostly likeable, but rather lifeless, main protagonists roaming the underworld in Blade Runner (Rick Deckard) or Blue Velvet (Jeffrey Beaumont), two heralded films from the ‘80s. How about Wendy and Danny Torrance in 1980’s The Shining? Did anyone think either would succumb to Jack’s ax wielding maniac? Didn’t we know that nothing was going to stop John Rambo in 1982’s First Blood? In contrast, we could always lose or be surprised by the sudden actions of other cinematic figures from prior decades such as Carol Ledoux from 1965’s Repulsion, Billy and Wyatt in 1969’s Easy Rider, Gloria Beatty in 1969’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, Eddie Coyle in The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), Travis Bickle from 1976’s Taxi Driver, Theresa Dunn in Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977) and so many others.

The same kind of invisible shield from innovation applied to many of the ‘80s comedies. Did any of the, say, Chevy Chase or Bill Murray films of the ‘80s come close to the risk taking, barrier bashing Putney Swope of the late ‘60s or Blazing Saddles in the ‘70s? Even today, scenes from the latter two films are recited all the time by movie lovers… and often, it seems, compared to any one of the numerous straight-laced or sophomoric comedies that came afterward. Regardless of what one might think of the immensely popular Ghostbusters (1984), was battling something so unidentifiable and imaginary that no one could possibly relate to or be the least bit affected by, going to cause any controversy? 1971’s Bananas on the other hand had a “revolutionary” topicality, a satirical subversiveness compared to the 80s’ less provocative approach to their humorous situations and populace. It wasn’t just Robert Downey, Mel Brooks and Woody Allen’s risk taking that invigorated the genre. What ‘80s flick can match the blatant irreverence of M*A*S*H or Where’s Poppa? (both 1970)? How about The Hospital, Little Murders, Taking Off, Carnal Knowledge (all 1971), The Groove Tube (1974), Shampoo (1975), The Bad News Bears (1976), or Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979) all joining those “mainstream appeal be damned” films that bucked like a blazing bronco the status quo? Finally, a special award goes to 1974’s Freebie and the Bean for its astonishing level of social impropriety, something I dare say we’ll never see the likes of again. For that matter, will we ever see a film resembling any one of these daring and provocative ‘70s comedies in our lifetime?

There is also a differentiation between three horror films that may provide a key as to how the existent creative environment affected each of their respective motion pictures’ conception and artistic integrity. The first was released in the late ‘60s, another during the ‘70s, and the last during the ‘80s.

As previously mentioned, the ‘60s started a trend of confrontational (especially regarding society’s traditional values, attitudes and behaviour) cinematic storytelling. The Night of the Living Dead (1968) joined in this cataclysmic disruption to our moviegoing sensibility. Anything could happen… and did.

The Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The Exorcist (1974) also managed to blow apart any previous preconception regarding its characters’ horrific crises as well as their responses to them. Naturally, this unorthodox film spawned a slew of inferior imitations.

The Exorcist (1974)

1987’s Fatal Attraction, however, after getting off to an incisive introduction of personal and situational complexity, about 1/3 of the way through, succumbed to an old “tired and true” genre conventionality, as if its filmmakers’ targeted viewership were the same as those who feed on formula.

Fatal Attraction (1987)

War Games (1983)

Another virus of audience relatability, concerning both its characters and situations, was injected into the “super computer gone rogue” scenario in 1983’s War Games, sacrificing authenticity for popular appeal whereas no such artificial affliction compromised the thematically comparable storylines in either 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or 1970’s Colossus: The Forbin Project.

2001: A Space Odyssey

Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970)

At Close Range

The adolescents in War Games were not the only youthful subjects of added appeal who cropped up during the 80s. Notice how the camera practically fawns over Sean Penn’s disaffected young man in the opening scenes of At Close Range (1986) or inordinately lingers on each one of the rebellious detention attendees throughout The Breakfast Club (1985) the latter of whom, at times, practically perform for us.

The Breakfast Club

The Last Picture Show

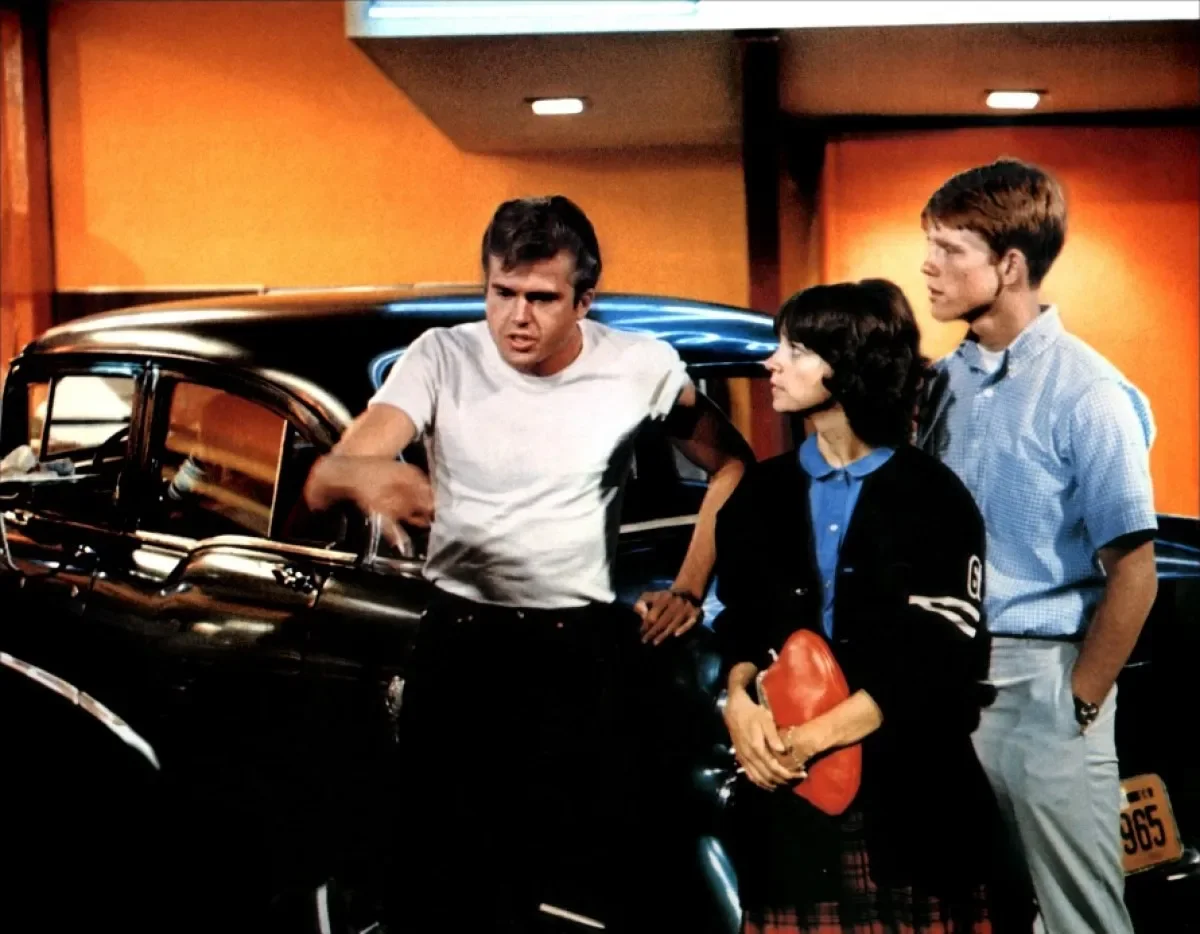

By comparison, the restless youth (albeit from an earlier time period) depicted in films such as 1971’s The Last Picture Show or 1973’s American Graffiti seem far more genuine; their situations less noticeably enhanced.

American Graffiti

Narrative predictability is a curse, even if it lies unaware in the subconscious, for both storytellers and their audience. We know it dulls the senses because the opposite excites them. The ‘80s announced an overwhelming number of films made for consumers as opposed to the previous decades in which a talented group of artists and craftspersons strived to tell unique personal stories regardless of their potential marketability.

One of the more persuasive indications of 80s producers relying on concepts to commodify their output are the sheer volume of sequels that began to flood the market (some of which were not based on original storytelling to begin with), a phenomenon corroborated by motion pictures such as:

Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie (1980, a sequel to 1978’s Up in Smoke), Nice Dreams (1981, a sequel to 1978’s Up in Smoke), Things Are Tough All Over (1982, a sequel to 1978’s Up in Smoke), Still Smokin (1983, still another sequel to 1978’s Up in Smoke), Oh, God! Book 2 (1980), Oh, God! You Devil (1984), Smokey and the Bandit Ride Again (1980), Smokey and the Bandit Part 3 (1983), Superman II (1980), Superman III (1983), Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1987), Friday the 13th: Part 2 (1981), Friday the 13th: Part III (1982), Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (1984), Friday the 13th Part V: A New Beginning (1985, so obviously the previous instalment was not the “Final” anything), Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives (1986), Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood (1988), Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan (1989), The Great Muppet Caper (1981, a sequel to 1979’s The Muppet Movie), The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984, a sequel to 1979’s The Muppet Movie), Halloween II (1981), Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers (1988), Airplane II: The Sequel (1982), Amityville II: The Possession (1982), Amityville 3-D (1983), Death Wish II (1982), Death Wish 3 (1985), Death Wish 4: The Crackdown (1987), Grease 2 (1982), Piranha Part Two: The Spawning (1982), Trail of the Pink Panther (1982), Curse of the Pink Panther (1983), The Black Stallion Returns (1983), Jaws 3-D (1983), Jaws: The Revenge (1987), Porky's II: The Next Day (1983), Porky’s Revenge (1985), Staying Alive (1983, a sequel to 1977’s Saturday Night Fever), The Sting II (1983), 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984, a sequel to 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey), Breakin' 2: Electric Boogaloo (1984), Cannonball Run II (1984), Cannonball Fever (1989), Conan the Destroyer (1984, a sequel to 1982’s Conan the Barbarian), Meatballs Part II (1984), Meatballs III: Summer Job (1986), Avenging Angel (1985, a sequel to 1984’s Angel), Angel III: The Final Chapter (1988), A Chipmunk Reunion (1985, a sequel to 1981’s A Chipmunk Christmas), The Chipmunk Adventure (1987, a sequel to 1981’s A Chipmunk Christmas), Howling II: Stirba - Werewolf Bitch (1985), The Jewel of the Nile (1985, a sequel to 1984’s Romancing the Stone), Missing in Action 2: The Beginning (1985), Braddock: Missing in Action III (1988), National Lampoon's European Vacation (1985, a sequel to 1983’s National Lampoon’s Vacation), National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989), A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 2: Freddy's Revenge (1985), A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987), A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master (1988), Loose Screws (1985, a sequel to 1983’s Screwballs), Police Academy 2: Their First Assignment (1985), Police Academy 3: Back in Training (1986), Police Academy 4: Citizens on Patrol (1987), Police Academy 5: Assignment Miami Beach (1988), Police Academy 6: City Under Siege (1989), Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985), Rambo III (1988), Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold (1986, a sequel to 1985’s King Solomon’s Mines), Hardbodies 2 (1986), The Karate Kid Part II (1986), The Karate Kid Part III (1989), Poltergeist II: The Other Side (1986), Poltergeist III (1988), Beverly Hills Cop II (1987), Creepshow 2 (1987), Deathstalker II (1987), Deathstalker and the Warriors from Hell (1988), Evil Dead II (1987), Ghoulies II (1987), Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II (1987), House II: The Second Story (1987), It's Alive III: Island of the Alive (1987), Revenge of the Nerds II: Nerds in Paradise (1987, not to mention III and IV which carried into the next decade), Slumber Party Massacre II (1987), Teen Wolf Too (1987), Arthur 2: On the Rocks (1988), Big Top Pee-wee (1988, a sequel to 1985’s Pee-wee’s Big Adventure), Caddyshack II (1988), Cocoon: The Return (1988), Critters 2 (1988, not to mention 3 and 4 which carried into the next decade), Crocodile Dundee II (1988), Ernest Saves Christmas (1988, a sequel based on 1987’s Ernest Goes to Camp, not to mention Ernest Goes to Jail, Scared Stupid, Rides Again, and Goes to School all of which carried into the next decade), Fright Night Part 2 (1988), Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), Iron Eagle II (1988, not to mention III and IV which carried into the next decade), The Man from Snowy River II (1988), Nightmare Vacation 2 (1988, a sequel to 1983’s Sleepaway Camp), Nightmare Vacation 3 (1989, a sequel to 1983’s Sleepaway Camp), Return of the Killer Tomatoes! (1988, a sequel to 1978’s Attack of the Killer Tomatoes!), Return of the Living Dead: Part II (1988), Short Circuit 2 (1988), Eddie and the Cruisers II: Eddie Lives! (1989), Fletch Lives (1989), The Fly II (1989), Ghostbusters II (1989), The Gods Must Be Crazy 2 (1989), Lethal Weapon 2 (1989, not to mention 3 and 4 that carried into the next decade), and The Return of Swamp Thing (1989, a sequel to 1982’s Swamp Thing).

Sure, we had sequels in previous decades (e.g. The Godfather Part II, The French Connection II, etc.) but hardly in these unprecedented numbers continuing all the way to the present with films like Mission Impossible Dead Reckoning Part 1 (foretelling of a sequel within a sequel to a number of sequels based on a reboot of a TV show), 2024’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes (the fourth sequel to just the 2011 reboot of the franchise), and Fast and Furious 1 to Infinity.

Since the early days of the art form, cinema lovers could revel in the artistic trajectory of their favourite Hollywood filmmakers from D.W. Griffith to Charlie Chaplin to John Ford to Howard Hawks to Fritz Lang to Anthony Mann including other distinctive masters of cinematic storytelling many of whom covered a wide variety of genres with equal aplomb. We had artists of immense individual creativity right up to and including the ‘70s where, for some filmmakers, conviction, innovation and passion reached their zenith. Hollywood’s emerging filmmakers in the ‘70s, for example, included the trio of illustrious trailblazers Robert Altman (e.g. 1970’s M*A*S*H*, 1971’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, 1972’s Images, 1973’s The Long Goodbye, 1974’s California Split, 1975’s Nashville) Hal Ashby (1970’s The Landlord, 1973’s The Last Detail, 1975’s Shampoo), and Francis Ford Coppola (1969’s The Rain People, 1972’s The Godfather, 1974’s The Conversation, 1974’s The Godfather Part II, and 1979’s Apocalypse Now).

And so I ask you: what comparable filmmaker, with even a shred of this threesome’s artistic vision (or any of the other previously mentioned voices of verisimilitude emanating from prior decades) were we able to take notice of in the 80s? Even those eminent filmmakers like Woody Allen and Martin Scorsese who each left their triumphant (albeit what seems like comparatively aberrational) imprint during this decade (Woody with 1984’s Broadway Danny Rose as well as 1989’s Crimes and Misdemeanors and Marty with 1980’s Raging Bull) first established their formidable presence with works from prior decades (Woody’s 1971 Bananas, 1979’s Manhattan and Marty’s 1973 Mean Streets and 1976’s Taxi Driver).

Considering the filmmaking climate that began in the late ‘70s and presided over the next decade, it’s a wonder we got as many noteworthy motion pictures as we did. In 1979 legendary film critic Pauline Kael wrote in great detail about the shift to corporate decision making that sadly ruled the ‘80s where so many films were made by committee and a test screening’s randomly selected audience (who probably, like the executives they were servicing, only had a few who knew anything about cinema’s history or diversity). In addition, these spectators collective feedback (a la 1982’s Blade Runner and 1987’s Fatal Attraction) could send motion picture executives into a panic demanding major alterations. The ‘80s initiated an environment where these kind of hatched events could thrive, contributing to the decade’s overall abundance of mediocrity. For example, our previously mentioned trio of artists comparatively floundered during this decade. Take for instance Robert Altman’s Popeye (1980) or 1987’s Beyond Therapy (before making a major stylistic comeback to form with 1993’s Short Cuts), Hal Ashby’s Second-Hand Hearts (1981) or Francis Ford Coppola’s most wantonly forgettable One from the Heart released in 1981.

Looking at the decade’s Academy Award winners, it appears these enviably honoured selections support Quentin Tarantino’s (and my own) claim of ‘80s “self-censorship” at least to some degree. The overall results seem blander and therefore less dramatically stimulating, thought provoking or memorable.

# Note: There are a few British films here, i.e. made outside of Hollywood (and therefore our critical parameters in this regard) that might shed more light on the Academy’s selection process during this decade than any preconceptions behind their making.

Ordinary People (1980)

… seems, more or less, aptly titled. Its narrative plods along in a calculated uneventful fashion trying so hard to avoid melodrama, the storytellers somehow manage to create an abundance of sentiment despite themselves. The discovery quotient, however, goes missing even among the enhanced feelings. Its first time director, Robert Redford (from Alvin Sargent’s adapted screenplay) has little of dramatic substance or the stylistic flourish of, say, a Douglas Sirk to compensate for his characters’ lack of emotional awareness making the filmmakers’ dispassionate approach to the material much like its subject matter. And since the film only covers the aftermath of tragic occurrences, we’re left to study their repressed reactions almost like clinicians, or at least from a detached perspective, rather than up close and personal or fellow travellers.

Chariots of Fire (1981)

… is well made and has integral characters but not really distinctive or conflicted enough to resonate beyond their chosen competitive circumstances. Hugh Hudson directed.

Gandhi (1982)

… is Richard Attenborough’s respectable biopic but lacks the driving force its central figure surely had to sustain such unshakable convictions. A comparison to 1962’s fiery, conflicted and passionate, not to mention ever evolving, Lawrence of Arabia seems appropriate in this context.

Terms of Endearment (1983)

… is lacking a thematic overview and is so unsure of where it’s headed, the filmmakers resort to programming a universally recognised affliction, i.e. a type of artificial demise, for one of its main characters. The purpose of inserting this sudden life threatening illness is to elicit some form of large sympathetic support before their aimless story ends, tailored for the more gullible part of an audience to remember their film by. James L. Brooks directed.

Amadeus (1984)

… is the most creative and imaginative of the winners listed. There’s no ‘let’s just stick to the historical facts’ here. The ingenuity behind a depiction of such a unique intertwining relationship between its two central composers originates from Peter Shaffer’s adaptation of his 1979 stage play which, some might opine, makes this a product of the previous decade. These characters offer endless fascination and both Tom Hulce (Mozart) and F. Murray Abraham (Salieri) could not be more suitable to conveying their characters’ honest emotions. (SPOILERS) Salieri’s scheme to orchestrate Mozart’s death, however, begins to look more and more like the playwright’s device than it does the composer’s true objective. In addition, Mozart’s wife leaving him only to return at the end and berate Salieri for helping her husband with his final composition is incongruous especially since that is the work Mozart was paid up front to compose, the one endeavour she most supported. Miloš Forman directed with confidence.

Out of Africa (1985)

… might as well be titled Out of Drama. Each encounter between characters is diffused of strife or invested feelings. Perhaps because this is based on a 1937 autobiographical book is why the whole enterprise feels so inert. Many filmmakers telling a true story (unlike those behind 1984’s winner) become apprehensive about sufficiently dramatising these types of narratives preferring instead to “stick to the facts” which so often translates into dramatic dullsville for the audience. What a shame the filmmakers had to resort to back-projection for its major set piece: a scenic flyover with our two stars. Even a much older George Peppard might have been better cast in Redford’s role since A) there wasn’t much of a character to portray no matter who was chosen and, more importantly, B) he was an accomplished pilot which could have made those shots of him and Meryl Streep in the plane far more authentic hence less wince inducing. Without John Barry’s luscious score, along with Amadeus’ divine Clarinet Concerto, watching this film would be tantamount to observing an elephant transverse the continent. Sydney Pollack directed.

Platoon (1986)

… depicts two distinct and opposing forces in Elias, the good guy (Willem Dafoe) and Barnes, the bad guy (Tom Berenger), along with a few harrowing scenes involving Vietnamese civilians. There are confrontations with the Vietcong that are chaotic and realistically presented so that the viewer can easily grasp Chris’ (played by Charlie Sheen) disorientation when he and his fellow soldiers fight an enemy they often cannot see and therefore distinguish from “friendly fire” or, in other circumstances, non-combatants. Chris is, however, too confused, his behaviour erratic and ineffectual, making it impossible for us to fully relate to his developmental journey. He’s portrayed as an innocent: someone to pity (a big ask considering the cruel acts his platoon is perpetrating on Vietnamese villagers including children) since he’s caught up in something unfathomable and mostly repulsive to his nature. As with almost all of the films about the Vietnam War, questions over why the U.S. is there or the country’s prolonged involvement go unanswered, a topic filmmaker Oliver Stone (no stranger to political controversy) was certainly capable of addressing (for example, see the same year’s Salvador, the next decade’s JFK, or his 2012 documentary series The Untold History of the United States). * So despite the realistic chaos depicted, along with the dramatically embellished discord among its soldiers, Platoon fails to make as lasting of an impression as the filmmakers were evidently striving for. **

* Three years later, Oliver Stone, with a firmer sense of direction, charted a young Marine’s transition (Tom Cruise as real life Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic) from blind patriotic duty to anti-war activist in 1989’s Born on the Fourth of July. The distance between these two ways of thinking prove, by what is shown, too great to be made convincing. This is due to Stone relying on Kovic's post-war highly charged personal interactions (most of which are insufficiently resolved) that have little to do with the young man's greater awareness of what that particular war was about. More attention, therefore, needed to be directed toward the cause of Kovic’s attitude reversal regarding the Vietnam conflict... a war that was started and sustained due to factors, as previously stated, fictional filmmakers seem reluctant to examine. Even at the end, when Kovic is about to address the Democratic Convention, simply hearing a part of his speech might have gone some way to understanding this individual's drastic turnaround of convictions.

* * Platoon makes for a fascinating comparison to 1978's The Boys in Company C especially since the latter was made during its decade of daring creative effrontery. The members of Company C's platoon are individually outlined through a series of ongoing multi-dimensional interactions and conflicts not only between themselves and their superior officers but in response to certain assignments, most of which relate to the unruly Vietnam campaign in particular. Scenes that take place during the inductees' boot camp training and wartime experiences have a frightening level of both implied and realised consequence. Canadian director Sidney J. Furie's film is, to be sure, messier i.e. inconsistent in tone, characterisation, story and situational development than Oliver Stone's more polished, even-handed and easier to assimilate Academy Award winning counterpart but still provides the more engaging and relevant watch with edgier rebelliousness... disputes that often occur simultaneously and usually with greater moral and political ramifications. The Boys in Company C also shares its two-part structure with Stanley Kubrick's 1987 Full Metal Jacket (as well as actor R. Lee Ermey's dynamic drill instructor). And once again, Furie's film is less refined and focused than Kubrick's military imputation. At its conclusion, however, The Boys in Company C manages its own cogent condemnation of a country's severe collective and individual humanitarian cost of entering into another's civil war. And it does so with a uniquely personal, no holds barred, 1970s kick.

The Last Emperor (1987)

… is hard to believe was directed by the same person who dazzled us with 1970’s The Conformist. An 80’s temperament of restraint and refinement in charting external historical influences on the title character’s life has taken over the unbridled vigour in exposing his main protagonist’s internal Sturm und Drang so illustriously illustrated in Bernardo Bertolucci’s earlier film.

Rain Man (1988)

… is Barry Levinson’s episodic odyssey of one man’s discovery of… wait for it: deeper feelings for his brother. Unfortunately, none of the pair’s, albeit lively, adventures successfully connect to this final enlightenment. On reflection, they look like little escapades that only serve the Tom Cruise character’s self-interests and act as a set-up for the audience’s amusement. In addition, both actors (Dustin Hoffman plays Cruise’s brother) combined efforts to emphasise their roles’ idiosyncrasies help make the whole enterprise feel laboured and unnatural.

Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

… depicts a growing friendship between its title character, an elderly Jewish woman in the 1950’s American South, and her black chauffeur. The racial divide, so prevalent at that place and time, is like other elements that are introduced but go unexplored. The filmmakers slight these narrative choices and others, including an off-screen bombing of a synagogue, by focusing on the gentle optimism and nostalgic amicability of its central relationship. This is still another film from the 80s that “plays it safe” by undermining the very aspects of importance and relevance its storytellers decided to introduce.

Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981)

It’s essential to remind readers that when exploring the cinematic landscape of any decade, there are always films that stand out from the crowd. One would assume Quentin Tarantino, and most certainly myself, are addressing each decade’s output overall, observing trends and uncovering possible reasons behind them. And again, I am referring to Hollywood fare as there are many distinguished films from other countries without a discernible “need to please” or “don’t stray too far off the beaten path” bone in their body. For instance, Canada’s Dead Ringers (1988) remains a formidable entry in the horror genre while Australia’s Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981) was arguably the most creative and compelling film of the decade. Plus, the latter was a sequel no less!

Raging Bull (1980)

Some of the more notable U.S. films from the ‘80s, made with integrity, consist of the following. In the documentary category, On Company Business (1980), The Atomic Cafe (1982), America: From Hitler to M-X (1982), The Times of Harvey Milk (1984), The Thin Blue Line (1988) and Central Park (1989, although fairly lightweight for documentarian Fredrick Wiseman) are standouts. In various genres as well, e.g. War: Full Metal Jacket (1987), Comedy: Airplane! (1980), A Christmas Story (1983), This is Spinal Tap (1984), and Lost in America (1985), Fantasy/Adventure: Excalibur (1981), Flesh+Blood (1985, with its unbridled abundance of both), Horror: A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), The Hitcher (1986), Thriller: Eye of the Needle (1981), 10 to Midnight (1983), Crime: Prince of the City (1981), Body Heat (1981), The Border (1982), The Star Chamber (1983), Flashpoint (1984), To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), and Manhunter (1986) come to the fore.

Do the Right Thing (1989)

There’s Louis Malle’s remarkable outlier character study Atlantic City (1981), Michael Mann’s gritty crime thriller Thief (1981), Ulu Grosbard’s masterclass in directing actors True Confessions (1981), Ted Kotcheff’s piercing consideration of a cult leader’s effect on a young man’s mindset in Split Image (1982), John Carpenter’s claustrophobic monster on the loose The Thing (1982, a Tarantino favourite), Marshall Brickman’s endearing little romcom Lovesick (1983), Sergio Leone’s elegiac gangster epic Once Upon a Time in America (1984), Stuart Gordon’s outrageous redefinition of horror Re-Animator (1985), Tim Hunter’s incisive examination of juvenile apathy River’s Edge (1986), Oliver Stone’s irascible political drama Salvador (1986), Bob Clark’s savvy mix of comedy antics and courtroom theatrics From the Hip (1987), David Mamet’s potent Neo-noir House of Games (1987), John Sayles’ socially impactful independent film Matewan (1987), Kathryn Bigelow’s audacious vampire movie Near Dark (1987), Joseph Rubin’s Hitchcock homage The Stepfather (1987), and Woody Allen’s masterful blend of seriousness and satire Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989). Finally, there was Raging Bull (1980), Martin Scorsese’s intense biopic which opened the decade, and Spike Lee’s assessment of racial unrest Do the Right Thing (1989) that closed out the 80s, both in superb fashion.

(To be continued… )

All responses are not only welcomed but encouraged in the comments section below.

Hope to see you tomorrow.

A.G.