Dish of the Day

Just some film musings of a more succinct, spontaneous and sometimes seditious nature:

Thursday, February 23, 2023

Today, I’d like to offer some quick thoughts on a trio of films from the ‘70s that are inspired by posts having arisen in various film related Facebook chat rooms (readers are encouraged to join the Cinema Cafe’s movie discussion room here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/902349343110685).

Death in Venice (1971)...

benefits from its languid and observant approach enhanced by sumptuous visuals perfectly aligned with classical composer Gustav Mahler's evocative music (most prominently the breathtakingly gorgeous Adagio from his Symphony #5). Watch closely and you'll find that the fictional composer’s (a perfectly modulated performance by Dirk Bogarde) interest in young Tadzio is not prurient in nature (as some have claimed). * His concern is for the boy’s safety, or perhaps in a less literal sense, preservation, which is really what this film is about: preservation of beauty, art and life when all around us are signs of decline, decay and death, both spiritual and physical. This is Luchino Visconti’s ode to aesthetic grace: simple, a bit too cautionary perhaps, but bathed in sublimity nonetheless.

* In Mahler (1974) director Ken Russell briefly parodied Visconti’s depiction of his fictional composer’s personal interest in the young man.

The Mechanic (1972)

The most artistically creative element in The Mechanic is its musical score by Jerry Fielding, sophisticated and enveloping. This enigmatic quality is also represented in the opening scenes with star Charles Bronson. About the mid-way point, however, The Mechanic tanks. The serious exploration of Bronson's character including the psychological afflictions of his career choice become The Mechanic’s abandoned storytelling tools by the time a newly hired protégé (played by Jan-Michael Vincent) decides to engage his mentor in killer versus killer one-upmanship, switching the narrative over to a stoic standoff. Even a superficial theme or study of personal behaviour is assassinated by the time Bronson and his supposed apprentice reach Europe with some desperately added cartoon-like antics inserted for who bloody knows what reason. Michael Winner's film ultimately becomes a loser. Of course that didn’t stop a remake in 2011.

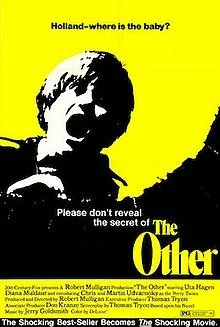

The Other (1972)

This solid but subtle, critically undervalued thriller is evocative and engaging. Seasoned director Robert (To Kill a Mockingbird) Mulligan builds the suspense and delineates his characters with restraint, care and precision as he did with 1968’s The Stalking Moon. Similar to what Roman Polanski was able to achieve in Rosemary’s Baby (also from 1968) director Mulligan creates a rare resonant truthfulness by carefully focusing on his characters’ thoughts, responses and emotions instead of emphasising the acts of terror so typical of lesser filmmakers working in this genre. Jerry Goldsmith’s nostalgic score blends harmoniously with the pastoral autumn setting, beautifully captured by Robert L. Surtees’ cinematography.

All responses are not only welcomed but encouraged in the comments section below.

Hope to see you tomorrow.

A.G.