Opening Up a Treasure: Vertigo

The reviews in this series are meant for those who have already seen the films in question.

Vertigo

U.S.A. / Paramount / 1958 / Technicolor / 129 Minutes (1996 Restored Version) / Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1 (Blu-Ray Version)

The hands of a wanted criminal grip a building's ladder as he desperately tries to flee across city rooftops from San Francisco's finest. During the chase, one of the detectives, John 'Scottie' Ferguson, fails to successfully make the leap from one building to another and finds himself hanging on to a gutter many stories above the ground below. Another officer stops to help, pleading with him to "Give me your hand" but slips and falls to his death.

In the next scene, we see Scottie in his friend Marjorie 'Midge' Wood's apartment recovering from his injuries. They speak of a prior "called off" engagement, his retirement from the force, her sketching of a strapless brassiere (referencing a real-life design ordered by Howard Hughes no less), his fear of heights, and guilt resulting from his fellow officer's death. Scottie's pronounced fear or acrophobia, which triggers vertigo, will factor into many of the major developments in his life-changing journey right up to its circuitous, tragic conclusion.

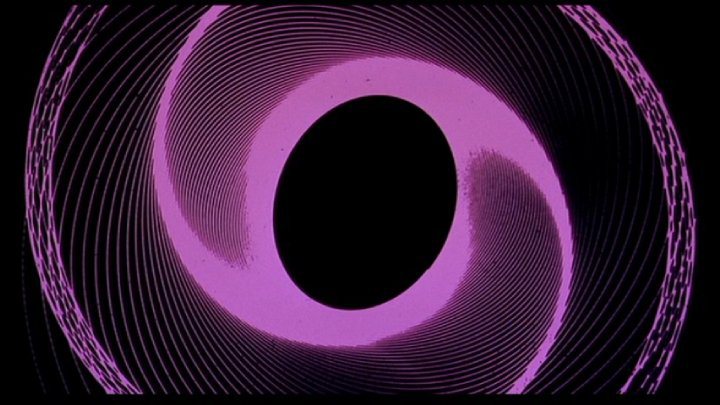

The film's title acts as a metaphor, representing an enormous spinning wheel that will produce an intricate web of mystery and obsessive love. Its meaning is enhanced by a circular themed score creating a dizzying design trapping the central character in fear both envisioned and realised. An offhanded remark by Scottie to Midge foreshadows a meeting that will unwittingly nudge this ex-officer right to the precipice of an unimaginable downward spiral: a phone call received from an old college buddy, Gavin Elster, who's "... probably on the bum and wants to set you for the price of a drink" as Midge predicts.

Nothing about Elster being broke or having such a simple request could be farther from the truth. Married into the ship building industry, he's wealthy and powerful but curiously yearns for earlier days when men had even greater power and freedom. He thinks his wife, who behaves most strangely, is possessed by a deceased spirit of her family's tragic past and wants Scottie to investigate her days "wandering" before committing her for psychiatric evaluation. Scottie wants no part of it, suggesting both Elster and his wife are crazy. Gavin, however, thinks, if Scottie will only see her, he might change his mind.

At a restaurant called Ernie's (practically a San Francisco landmark at the time and the first of many to be visited), Scottie sits at the bar observing Gavin and his wife dining. As they leave, he gets his first clear look at Madeleine Elster presented in a stunning profile of refined, radiant and practically unobtainable beauty. His prior thoughts of not wanting to "... get mixed up in this darn thing" escape faster than Houdini. Madeleine is portrayed by Kim Novak, perhaps the only actress at the time capable of capturing her character's classic allure possessing the simple but sophisticated elegance needed to convincingly melt away the retired detective's hardened resolve. Scottie sees that luminescent profile and we know he's a goner. She even "floats" out of the restaurant, to the warm embrace of Bernard Herrmann's delicately sentimental motif as if she isn't real... which in a way she isn't. In a brilliant edit, we cut right from Scottie's observation to being on the case. His former skepticism has instantly transformed into primed dedication as he anticipates Madeleine's appearance outside her luxurious apartment high-rise and his chance to follow her to the locations she frequents. Little does he know that his turnaround is the beginning of a free-fall down a rabbit hole of romantic infatuation, treacherous deceit, death and madness.

Scottie is played by James Stewart who during the course of his investigation and subsequent romantic involvement will be required to perform the decathlon of emotionally enhanced responses, especially during his character's vertiginous experiences, and Stewart gets the gold every time. As he follows Madeleine to a flower shop, a cemetery where her suicidal great-grandmother Carlotta Valdez is buried, a museum where she sits and stares at a portrait of Carlotta and an old hotel where she often uses Carlotta's name when checking in, we become increasingly mesmerised by the hold these places (not to mention Carlotta's spirit) have on Madeleine. This intrigue spills over into Scottie's temperament as he continues his investigation. With Midge's help, he visits an old bookseller, an authority on San Francisco's lurid history who tells of Carlotta's deep depression and tragic suicide after her husband kept their child but "Threw her away." He adds "A man could do that in those days. They had the power... and the freedom," eerily echoing Gavin Elster's nostalgic fantasy of living in those times. Scottie dutifully reports his subject's itinerary and haunted past to Gavin who tells him that Madeleine has no idea who Carlotta is, or any remembrance of the specific places she visits, firmly stating "She's no longer my wife."

This beginning voyeuristic odyssey taken by our protagonist is cherished ground for the film's director Alfred Hitchcock. Hitch likes to analyse his subjects' behaviour but also observe their perspective. He'll endlessly watch Roger Thornhill wait to meet someone out in the middle of nowhere in North by Northwest or Melanie Daniels deliver some love birds in The Birds' protracted uneventful opening. His legendary characters who spy on others like Jeff Jeffries' photographer in Rear Window or Norman Bates' peeping-Tom in Psycho plus his constant traveling point of view shots provide ample evidence of this claim. Sophisticated as Hitchcock's filming techniques are, and maturely crafted as his storytelling is, he's never had the chance to plumb the psychological depth of a character's soul until Vertigo and courageously takes full advantage of this prime opportunity. Instead of watching his central character routinely react to the narrative's surprises from a detached perspective, Hitchcock magnetises Scottie. He wants us to feel what he feels, think what he thinks and react the way we know he will. Perhaps it's the ingenious screenplay that helps draw us into this retired detective's world from the novel D'Entre les Morts authored by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. This was written after Hitchcock expressed admiration for a prior work of theirs made into the film Les Diaboliques. Of course there's assistance by the best of a seasoned crew of collaborators including screenplay adapters Alec Coppel and Samuel A. Taylor, the aforementioned Bernard Herrmann's lush romantic score (one of the most emotionally expressive ever composed for a motion picture), Robert Burks' enthralling cinematography and George Tomasini's precise editing.

On another day of following Madeleine around the city where she ventures to a new location, Scottie can no longer just sit back and observe. He's required to act. Madeleine, seemingly in one of her trances, suddenly attempts suicide by jumping into San Francisco Bay and Scottie, being the only person around, must save her. Taking her back to his apartment, he removes her wet clothes as she lies unconscious and lets her sleep. She awakens when the phone rings appropriately shocked to be lying naked in a strange man's bed. Scottie lies to her by saying he just happened to be in the area wandering when she "fell" into the bay, and thus the first seeds of deception between the two are apparently planted by Scottie... ironic considering what he will be forced to deal with later. During their brief fireside chat, we sense the subtle feeling of attraction between Scottie and Madeleine that will later blossom into a full-fledged romance. The next day, Scottie is back to following her around the city but this time, much to his exasperation, she seems to be driving in circles without a clue. When Madeleine finally winds up at Scottie's apartment to apologise for all of the trouble she's put him through, specifically the embarrassment of having to remove all of her wet clothes, Scottie enthusiastically replies, "No, I enjoyed...[now plaintively] talking to you" cutting himself off from really embarrassing himself. They decide to wander together.

The scene that will most solidify Madeleine's obsession with death, together with the couple's new found amorous relationship, takes place in the Muir woods outside the city. These giant redwoods literally mean "Always green, ever living" and vividly contrast Madeleine's haunted spirit telling her she must die, not to mention Scottie's insatiable need to keep her safe and try and solve the enveloping mystery. This is a spectacular scene. Submerged in the atmosphere of the forest's mystical surrounds and then the nearby ocean's stirring beauty are Madeleine's almost sudden disappearance, her temporary trance-like state of mind, symbolic references to life's transitory nature, a strange dream of a bell tower in Spain and strong declarations of desire. The scene ends when the two passionately kiss and embrace as the ocean waves crash behind them. Absolutely splendid!

At Midge's apartment, Scottie's relationship with her becomes strained when she persists in asking about his activities and makes fun of his absorption in ghostly pursuits particularly in a funny moment involving one of her paintings. Midge is expertly portrayed by Barbara Bel Geddes who is quite attractive herself but whose character is the antithesis of Madeleine. Dressed plainly with glasses, there's no mystery about her. She's the analytical one who can spot something phoney 10 miles away. Despite being the character who demonstrates the most honest love and compassion for Scottie, she cannot compete with the enigmatically seductive Madeleine. Midge is, in terms of deconstructing mystery, too much like Scottie’s doppelgänger. That’s Scottie’s department. He wants to save Madeleine, not be saved from her. Bel Geddes’ character is, however, vital to this story. Adding her refreshingly no-nonsense perspective speaks for those who still harbour some doubt as to the overall validity of what's been presented and more importantly, boosts our confidence in that the story's ethereal, romanticised aspects will not cause the narrative to lose its credibility. Normally we could depend on Scottie for some levelheadedness but he's too consumed with emotion and walks out on Midge.

Back at home, he gets a surprise visit from Madeleine who speaks of the dream again involving a bell tower. This time, however, Madeleine describes details that Scottie recognises as real. Furthermore, he insists she's been to this place before, the location of which is about 100 miles south of San Francisco. He'll take her there in an attempt to fight the possessive spirit of the past with the harmless reality of the present just like a good detective should. When he does, however, events will suddenly turn tragic. After showing Madeleine around the picturesque San Juan Bautista Mission in an attempt to persuade her that there's nothing harmful about wooden horses or anything else she's seen and then dreamt about, Madeleine, after apparently succumbing to one of her hypnotic states, says "It's too late" and suddenly bolts across the lawn. She leads Scottie to the small church begging him in an unfamiliar, demonstrative tone to let her enter alone adding "It wasn't supposed to be this way." Kissing and embracing, she declares that she will forever love him and runs inside with Scottie looking up to see the tower... a shocking reminder of his otherwise forgotten acrophobia. His pursuit of Madeleine is as futile as the criminal in the film's opening. He tries to make his way up the stairs after her but, as we see in a wicked display of photographic ingenuity, cannot handle the frightfully difficult ascent to the top and from a small opening in the tower, watches in horror as Madeleine falls to her death.

The second phase of the story begins with a court inquiry into the circumstances surrounding Madeleine's death. Scottie is commended for saving her life during her first suicide attempt but admonished for not making a greater effort the second time and shamefully leaving the scene. Her death is ruled a suicide so he is ultimately free to go but before leaving with his former superior officer, receives a few encouraging words from Gavin Elster who tells him: "He [the judge] had no right to speak to you like that. There's no way for them to understand. You and I know who killed Madeleine" implying Carlotta's spirit finally managed to do her in. If Gavin’s words of consolation are sincere, there’s an ever-so-slight silver lining to Madeleine’s death: Scottie no longer has to confront Gavin over his betrayal of romantic involvement with his wife.

A mournful Scottie visits Madeleine's grave. That night, lying in bed, it becomes his turn to be haunted with a frightening nightmare of death. Appearing before him are voracious visions of the bouquet in Carlotta's portrait disintegrating, Gavin standing next to Carlotta, Scottie making his way to Carlotta's now empty grave then descending into its darkness, caught in a vortex and finally, falling from the bell tower in Madeleine's place. It's a bravura scene of terror accompanied by Bernard Herrmann's feverish staccato-like and sinister score.

Scottie's remorse over Madeleine's death leads to his acute melancholia and being institutionalised. Midge is there but she cannot help. He's ashen and catatonic. Her heart-felt feelings for Scottie are poignantly evident and in a lovingly captured long shot, slowly leaves the hospital alone.

About a year has passed and after being released, Scottie visits Madeleine's old haunts. At each one he constantly projects her likeness on to other women he sees. (At this point, some viewers, engrossed in identifying Scottie’s former burning desire to solve an unsolvable mystery, may wonder where he and this story can possibly go.) Then, outside the flower shop Madeleine visited, he sees another woman with a resemblance to Madeleine. In his bewildered and forlorn state, he follows to her apartment, knocks on the door and begs to ask a few questions. Her name is Judy Barton and while the physical resemblance to Madeleine is striking, her personality, ordinary clothes and drab surroundings are completely different. Scottie manages to talk her into seeing him later that evening. It seems as though Judy has taken some pity on him after finding out that she resembles someone he loved who died but there's more to it. After he leaves, the scene oddly continues with Judy alone. She slowly turns to the camera with a look of fear mixed with concern and stares into nothingness remembering something of astonishing relevance. The music and image suddenly darken red signalling one of cinema's greatest flashbacks: a powerful vision that chills to the bone turning everything on its head that we've previously witnessed and transforming our view of the events about to occur.

After learning the truth about the former proceedings, we will enter the third and most intimately analytical act of Scottie's incredible odyssey. Hitchcock received some flack from critics for exposing the mystery at this point in the story but it was the right choice allowing the audience to gain an acute observational perspective of Scottie and zero in on his increasingly pronounced new-found desire to make Judy over to look and act like Madeleine. This is a momentous opportunity to watch a character ad extremum, one we've come to know deep down to the souls of his shoes, now with an incredible topsy-turvy insight into a reality he doesn't possess. A key foreshadowing moment of Scottie's Pygmalion-like cause occurs when he takes Judy out on their first dinner date. Where would he take her? Ernie's of course but that's not all. He still sees hallucinatory images of Madeleine projected on to other women even though he's now with Judy. It's as if Scottie is so consumed with Madeleine, he's also carrying the torch of her prior obsession with death. Furthermore, his desire to stop Carlotta's spirit from inhabiting Madeleine ironically opposes his yearning for Madeleine's to inhabit Judy. At several stages Judy protests, repeatedly asking why he can't love her for who she is. Scottie professes his love for Judy as well. Nevertheless, his compulsion with reviving Madeleine mounts as he imposes details of her appearance on to Judy beginning with a flower pin, then Madeleine's exact outfits, even her shoes.

After a few days spent dancing and taking in San Francisco's picturesque sights, Judy's complicity in Scottie's cause designed to win his love starts to take on a sympathetic dimension even though we know she's holding back vital information. Her character's added feelings of worth that we gradually want Scottie to recognise also indicate that, in order for Scottie to revive Madeleine, Judy must be sacrificed. That hardly seems like the operative word, however, since in comparison Scottie demonstrates far more depth of feeling for Madeleine than he does for her potential second-rate host. Judy desperately asks about her transformative process "What good will it do?" Scottie stubbornly admits "No good I guess" momentarily suggesting his project's defeat. That is, until he becomes transfixed with her brunette hair and like Svengali says hypnotically "The colour of your hair" taking his mania to almost necrophilic heights. His comment is so possessive and drastically selfish, it typically solicits laughs from the audience. He even adds emphatically "It shouldn't matter to you."

Finally, Judy returns to her apartment after she's reluctantly gone through with all of Scottie's numerous demands to revive the dead Madeleine. She's had her make-up professionally done according to Scottie's explicit specifications and hair bleached blonde (a tip of the hat to Hitchcock's penchant for hiring beautiful blonde actresses). Even so, he complains about her hair style saying it should be pinned back causing Judy to retreat to the powder room. Then there's a moment of sheer splendour. As Scottie anxiously awaits her appearance, the music suddenly swells, and Judy emerges completely as Madeleine wearing the grey suit she wore just before her death. She's reborn, signified by bathing in a powerful green neon light from just outside her apartment's window so strong, in fact, it gives her a ghost-like appearance. She even walks like Madeleine over to a wide-eyed Scottie, desperately longing for his loving acceptance which she gets, and how! They embrace and kiss over and over as the camera revolves around them. Scottie only pauses slightly as he observes Judy's drab apartment magically transform into the livery stable just outside the church where he last held his dear Madeleine. The setting changes back as the couple share their passionate feelings for one another culminating with Herrmann's piece de resistance: a rhapsodic variation of the thematically comparable Wagnerian opera Tristan und Isolde climaxing in a breathtaking crescendo.

Scottie's success of reviving the dead has wiped out his regrets and mournful past feelings. Judy, who's at least retained a few of her own personality traits, and he are now starting to look like your average couple in love. As they engagingly anticipate another dinner at Ernie's or "... our place" as Judy enthusiastically intones, she puts on a necklace and her entire charade is over. Scottie figures out what we have known since witnessing that eventful flashback and tricks her into going "... somewhere out of town for dinner" instead. It's out of town alright but they don't serve food at the San Juan Bautista Mission where Madeleine met her demise.

The scenes that follow will reach the summit of storytelling finales in one of the most deeply profound and enlightening explorations into both the darker and romantic side of the human psyche ever recorded on celluloid. There's plenty of meaningful elements to admire and ponder after witnessing Vertigo. Aside from the creative twist that's used in the flashback, there's the symbolic use of red (death) and green (birth) colours, falling, repetition and circular motifs in the imagery and music. Mirror images are both seen and mentioned. Back to front exposition abounds: the supernatural turns into the most common of human incentive, fantasy interlocks with reality, passion contends with subterfuge. There's the downward direction Scottie travels when following Madeleine to his apartment, and repeated references to the term "wander," a metaphor for aimlessness when there's really anything but, going on in this story. Still other aspects to consider are Gavin Elster's motive behind an ingenious grand design including Judy's subsequently successful part in that plan. She deceitfully solicits and secures Scottie's emotional transference to Madeleine only to plead for a complete reversal back to herself at the end of the story. Then there's Scottie's magnificent obsession with, and failure in, saving Madeleine and imagining her as Judy. He finally pulls out all the stops (with a "best scene" performance by Stewart) in brutally punishing Judy for her complicity in Gavin's ruse, literally dragging Judy to a place he did everything to keep her from going to earlier. During this final scene on the stairs, Scottie’s vindictiveness toward Judy is so pronounced it seems he’s holding her solely accountable for destroying his romance with Madeleine! Despite Judy’s romantic appeals and reasoning, he protests saying “It’s too late” mirroring the same words Judy spoke as Madeleine before she entered the bell tower for the first time. Scottie appears to finally succumb to Judy's desperate desire for his love and acceptance signified by their full embrace and passionate kiss but it's not the final act nor does Scottie get the final say.

Some so called "message" films are rightfully described as such because of a character or story development that symbolically relates to a greater truth about our existence and Vertigo is one of those films. Consider Scottie's relationship with Judy. His intellectual failure to separate compelling desire from illusion shouldn’t make his feelings less meaningful. Granted, they are outrageously intensified. If, however, we remove the unusual circumstances accounting for that intensification, doesn't the basic nature of those emotions seem a little familiar... or even admirable? Scottie's relationship becomes one of subconscious expectation of whom he wants Judy to be rather than who she is, and therefore calls in to question the basis for all romantic attraction: a subliminal suggestion reinforced each time Scottie projects Madeleine onto other women he sees. And what about Scottie's great discovery relating to the film's final moments? It's Judy he was really in love with all along; the penultimate irony being Judy’s complicity in Madeleine’s death. This is a point only topped when, in Scottie’s final vow of adoration, he calls Judy… Madeleine! So what is "love" anyway? Is it really the person we're in love with or our projections we unwittingly superimpose on another that we're drawn to? Can those same unleashed desires dictate other life experiences? Have these storytellers given us something to think about or what?

Some have wrongly identified Vertigo as film noir. Psychology, mystery, romance or a combination of the three but not noir. It may have noir elements, namely Gavin's real intentions, but those criminal components only come into play late in the game and are not the story's focus even afterward. Vertigo would be noir if told from Gavin's point of view but as things stand this is Scottie's story (so much so that even a Production Code imposed ending involving Gavin was thankfully dropped) and Scottie's is all about love, twisted and possessive as it may be. Plus, there is never any indication that Scottie would even consider committing a crime (an essential element in film noir) to further his goals or interests. Romance is the film's heart and soul, resulting in that genre's most enlightening achievement.

If all of cinema is an illusion then Vertigo is its grandest. Being such an overtly (albeit meticulously) contrived story, however, prevents it from achieving the international artistic success afforded to Citizen Kane, despite the 2012 British Film Institute's Sight & Sound critics poll announcement of Vertigo finally topping Citizen Kane as the greatest film of all time. Some detractors have called Vertigo “a fraud" and there is some truth in that. It's aggressively but expertly manipulative, presenting intricately devised situations and characters, a perfectly chosen cast who all deliver honest and dedicated performances and will forever resonate for those who commit to its meritorious entrancing qualities. Rich in profundity, Vertigo improves with age and becomes more rewarding after each viewing forever revealing new insights. Like other great romantic tragedies, this cinematic story confirms the impossibility of idealised love while at the same time enticing us with its intoxicating essence. For hopeless romantics, Vertigo is the ultimate aphrodisiac with some of us practically becoming as obsessed with the film as Scottie does with Madeleine. The film's influence on other directors can be seen in their works, most notably Brian De Palma's Obsession, Mel Brooks' parody High Anxiety, and David Lynch's Mulholland Drive.

Vertigo's final image signifies a journey's end: Scottie's conquest over his fear of heights has finally come but at a terrible price, i.e. his life's purpose. Before the final fatal moment occurs, Scottie faces a price he refuses to pay, to let go of his fantasy romance with someone he never met, never even looked at. Only at the end when fate arrives in the form of a Nun who “heard voices” can the account be marked “paid in full.” The cost of fear is desire and in order to eliminate the first we must sacrifice the latter. This cinematic finale will thrive in our memories filling us with admiration and represents the finest of what can be achieved by a harmonious collaboration of amazing storytellers who fortunately chose film as their preferred medium.

A.G.

How To Best Appreciate This Treasure:

Currently its best presentation is on this Region A Blu-Ray:

It is also available on this Universal Region 1 DVD:

The film's original motion picture score by Bernard Herrmann is on this Varese Sarabande soundtrack: