End Credits #93: Cinema's 2019 Lost Treasures Robert Evans

The dynamic and accomplished Producer Robert Evans (June 29, 1930 - October 26, 2019) has died at age 89.

Guest contributor Bob DiMucci has provided a tribute to his motion picture career:

The Films of Robert Evans

Publicist Ralph Wheelwright and James Cagney sold the story of Lon Chaney’s life to Universal for their production of MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES. Norma Shearer, widow of Irving Thalberg, spotted Robert J. Evans, a young sportswear executive, in Beverly Hills and, noting his resemblance to the mogul, brought him onto the project to play Thalberg. Although it isn't pointed out specifically in the film, Irving Thalberg was the production chief at Universal, where Chaney made THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME, but then moved to MGM, where Chaney spent the majority of his career.

Robert Evans and Norma Shearer

Jeanne Cagney, who plays Chaney’s sister in the film, was Cagney’s real-life sister. Lon Chaney, Jr. wanted to appear in the picture, but the studio could not find a suitable role for him to play. The younger Chaney changed his first name from Creighton to Lon, Jr. in the 1930s, after appearing under his real name in many films.

James Cagney personally recommended Dorothy Malone for the role of “Creva Creighton Chaney” and Roger Smith for the role of the adult “Creighton Chaney. Years earlier, on a trip to Hawaii, Cagney had met Smith, who was stationed there in the Naval Reserve. Impressed with his clean-cut good looks and appeal, he encouraged Smith to pursue an acting career. Director Joseph Pevney originally was not interested in the film, but accepted the job after producer Robert Arthur agreed to allow him to direct TAMMY AND THE BACHELOR (1957).

Frank Skinner’s score was released on a Decca LP and was issued on a gray market CD by Disques CinéMusique in 2012.

The filming of Ernest Hemingway's 1926 novel THE SUN ALSO RISES had a long gestation period. Intending to star as "Lady Brett Ashley," in April 1934, actress Ann Harding purchased the rights to the novel, which follows a group of disillusioned American expatriate writers living a dissolute, hedonistic lifestyle in 1920s France and Spain. Leslie Howard was to play "Jake." In December 1944, Constance Bennett considered buying the rights from Harding, and planned to star in and produce the project for United Artists release. Howard Hawks purchased the rights from Harding in 1949. At that time, Montgomery Clift and Margaret Sheridan were to star in Hawks's production for Twentieth Century-Fox. In 1952, Hawks left Fox to pursue a career as an independent producer-director, and took the property with him, which he intended to produce in Europe starring Dewey Martin. By 1955, Hawks agreed to sell his interest in the novel back to Fox, but still planned to direct the film.

Correspondence between the would-be producers and the Production Code Authority (PCA) during these years reveals why the project was so difficult to bring to fruition: In Hemingway's novel, Jake's war injuries resulted in his impotence and Lady Brett was depicted as a nymphomaniac. The PCA deemed the issues of impotence and nyphomania as "not proper for screen presentation," and thought the novel to be "salacious," its characters "promiscuous and immoral."

After Fox bought the rights in 1955, a new approach to the topic was suggested that finally won approval from the PCA. Twentieth Century-Fox production chief Darryl F. Zanuck proposed dropping all explicit references to Jake's impotence, thus divorcing it from a specific physical reason and instead putting it in the abstract realm of a "war injury." Zanuck's other tactic was to portray Lady Brett's problem not as nymphomania, but rather excessive drinking. Although the project finally won approval from the PCA because of these changes, in the final film, in Jake's dream sequence, which flashes back to his time at the hospital, Jake is explicitly told by the "Doctor" (Henry Daniell), that he is impotent.

Henry King directed the 1957 film. The city of Morelia, Mexico doubled for Pamplona, Spain. Charles Clarke shot the annual running of the bulls in Pamplona. Location filming also took place in Paris and Biarritz, France. Zanuck directed some of the French sequences while Henry King was filming in Mexico. Some interiors were shot at the Estudios Churubusco in Mexico City.

Actor and future producer Robert Evans, who portrayed dashing young bullfighter "Pedro Romero" in the film, entitled his autobiography The Kid Stays in the Picture because, according to Evans, during production of THE SUN ALSO RISES, when King and others felt that Evans was not up to the role and should be replaced, Zanuck sent a telegram to King stating "The kid stays in the picture." Hugo Friedhofer’s score for the film was released on a Kapp LP and finally re-issued on CD by Quartet in 2018.

On the strength of his television stardom, Hugh O'Brian got his first lead role in a feature film in 1958's THE FIEND WHO WALKED THE WEST. O'Brian played bank robber "Dan Hardy." Dan is locked in a cell with “Felix Griffin” (Robert Evans), a psychopath who warns Dan never to touch him. Gordon Douglas directed the 20th Century Fox production. The film’s title came from a marketing executive trying to cater to both western and horror film audiences.

Robert Evans and Dolores Michaels in THE FIEND WHO WALKED THE WEST

The film was affected by the 1958 musicians' strike and used a stock music score, including tracks from Bernard Herrmann's THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL, much to Herrmann’s displeasure.

In director Jean Negulesco's THE BEST OF EVERYTHING, Robert Evans was part of an all-star cast. Evans is playboy “Dexter Key,” who drives “April Morrison” (Diane Baker), a naïve young woman in search of true love, back to New York in his snazzy sports car and then seduces her. Evans beat out Barry Coe for the part of "Dexter Key" in the 1959 film.

Robert Evans, Diane Baker, and Hope Lange in THE BEST OF EVERYTHING

Film Score Monthly released Alfred Newman’s score in 2001. Newman and Sammy Cahn's song "The Best of Everything" was nominated for an Academy Award, but lost to the song "High Hopes" by Jimmy Van Heusen (music) and Sammy Cahn (lyrics) from A HOLE IN THE HEAD.

Robert Evans was originally cast in the role of Italian-American policeman "Johnny Viscardi" in the 1960 film about the "Black Hand" PAY OR DIE!. But he abruptly left the cast and was replaced by Alan Austin. Dissatisfied with his own acting talent, he was determined to become a producer. He got his start as head of production at Paramount by purchasing the rights to a 1966 novel titled THE DETECTIVE, which Evans made into a movie for 20th Century Fox in 1968, starring Frank Sinatra, Lee Remick, Jack Klugman, Robert Duvall and Jacqueline Bisset. Peter Bart, a writer for The New York Times, wrote an article about Evans' aggressive production style. This got Evans noticed by Charles Bluhdorn, who was head of the Gulf+Western conglomerate, and hired Evans as part of a shakeup at Paramount Pictures (which included Bart, whom Evans would recruit as a Paramount executive).

When Evans took over as head of production for Paramount, the floundering studio was the ninth largest. Despite his inexperience, Evans was able to turn the studio around. He made Paramount the most successful studio in Hollywood and transformed it into a very profitable enterprise for Gulf+Western. During his tenure at Paramount, the studio turned out films such as BAREFOOT IN THE PARK, THE ODD COUPLE, ROSEMARY'S BABY, THE ITALIAN JOB, TRUE GRIT, LOVE STORY, AND HAROLD AND MAUDE.

Dissatisfied with his financial compensation and desiring to produce films under his own banner, Evans struck a deal with Paramount that enabled him to stay on as studio head while also working as an independent producer. Evans' first film as a credited Executive Producer was 1972' s THE GODFATHER.

According to Evans, Mario Puzo initially brought a twenty-page treatment of the novel to him that was entitled Mafia. Evans told the story that Puzo owed the mob $10,000 or so. Evans basically optioned the novel for the amount of money that Puzo owed the mob.

In January 1969, Paramount secured the rights to the novel, which by that time was listed as number one on the New York Times bestseller list. Various 1969 news items added that Paramount had purchased the book for a "bargain price" that would be spread out, based on the number of copies sold, to a maximum of $80,000. Decades later, in a July 2002 interview for a special Paramount anniversary issue of the Hollywood Reporter, Evans recollected that Burt Lancaster had wanted Evans to sell him the rights to Puzo’s novel for $1,000,000, but Evans turned him down.

Mafia crime boss Joe Colombo and his organization, The Italian-American Civil Rights League, started a campaign to stop the film from being made. According to Robert Evans in his autobiography, Colombo called his house and threatened him and his family. Paramount Pictures received many letters during pre-production from Italian-Americans, including politicians, decrying the film as anti-Italian. They threatened to protest and disrupt filming. Producer Al Ruddy met with Colombo, who demanded that the terms "Mafia" and "Cosa Nostra" not be used in the film. Ruddy gave them the right to review the script and make changes. He also agreed to hire League members (mobsters) as extras and advisers. The angry letters ceased after this agreement was made.

Paramount Pictures owner Charlie Bluhdorn read about the agreement in The New York Times, and was so outraged, that he fired Ruddy and shut down production, but Evans convinced Bluhdorn that the agreement was beneficial for the film, and Ruddy was rehired.

Several contemporary sources, including a Time article, reported numerous names of prominent actors who had been considered for principal roles in the film. Marlon Brando was the first publicly announced cast member, approximately two months before the start of principal photography. A Daily Variety news item chided Robert Evans for his statement in September 1970 that the film would be cast with "real faces" and not "Hollywood Italians." Although most contemporary and modern sources agree that Brando had always been the favored choice for "Don Vito," various other names mentioned for the title role in Time and other contemporary articles included Laurence Olivier, George C. Scott and Ernest Borgnine.

Robert Evans claimed that Brando was paid $50,000, plus points, and sold back his points to Paramount before the release of the picture for an additional $100,000 because he had female-related money troubles. Realizing the film was going to be a huge hit, Paramount was happy to oblige. This financial fleecing of Brando, according to Evans, is the reason he refused to do publicity for the picture, or appear in the sequel.

Martin Sheen and Dean Stockwell auditioned for the role of "Michael Corleone." Oscar-winner Rod Steiger campaigned hard for the role of Michael, even though he was too old for the part. Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, and Dustin Hoffman were all offered the part of Michael Corleone, but all refused. Suggestions of Alain Delon and Burt Reynolds were rejected by Francis Ford Coppola. Robert Evans wanted Robert Redford to be cast in the part, but Coppola demurred, as he was too WASP-y. Evans explained that Redford could fit the role, as he could be perceived as "northern Italian".

With Redford off the table, Evans insisted that James Caan be cast as Michael. At that point, Carmine Caridi was cast in the role of "Sonny." The Paramount brass, particularly Evans, were adamantly opposed to casting Coppola-favorite Al Pacino, who did poorly in screen tests, until they saw his excellent performance in THE PANIC IN NEEDLE PARK(1971).

Evans eventually lost the struggle over the actor he derided as "The Midget". Evans told Coppola that he could cast Al Pacino as Michael as long as he cast Caan as Sonny. Although Caan had been Coppola's first choice for Sonny, he later decided that Caridi was better for the role, and did not want to re-cast Caan. But Evans insisted on Caan because he wanted at least one "name" actor to play one of the brothers, and because the 6'4" Caridi would tower over Pacino on-screen.

Before Francis Ford Coppola was hired, Peter Yates, Richard Brooks, Peter Bogdanovich, and Costa-Gavras were approached by Robert Evans and Paramount to direct THE GODFATHER. All turned it down. Evans apparently screened the films about gangsters that Paramount Pictures had released before he arrived at the studio, including THE BROTHERHOOD (1968). He noticed that most of the films were unsuccessful, and also that they had not been written nor directed by Italian-Americans, and said that he hired Coppola in part, because he wanted to "smell the spaghetti".

Mario Puzo, Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Evans, and Al Ruddy

During pre-production, Coppola shot his own unofficial screen tests with Al Pacino, James Caan, Robert Duvall, and Diane Keaton at his house in San Francisco. Evans was unimpressed by them, and insisted that official screen tests be held. The studio spent $420,000 on the screen tests, but in the end, the actors and actresses Coppola originally wanted were hired.

At one point during filming, Evans felt the film had too little action and considered hiring an action director to finish the job. To satisfy Evans, Coppola and his son Gian-Carlo Coppola developed the scene in which "Connie" (Talia Shire) and "Carlo" (Gianni Russo) have their long fight. As a result, Evans was pleased enough to let Coppola finish the film.

Al Pacino and Robert Evans at the premier of THE GODFATHER

Coppola turned in an initial cut of the film running two hours and six minutes. Evans rejected this version, and demanded a longer cut with more scenes about the family. The final release version was nearly fifty minutes longer than Coppola's initial cut.

Even at that length, James Caan was angry that scenes giving "Sonny" more depth (such as his reaction to his father's shooting) were cut from the film. He confronted Robert Evans at the premiere and yelled at him, "Hey, you cut my whole fuckin' part out". Caan claimed that forty-five minutes of his character were cut.

Robert Evans, Ali MacGraw, and James Caan at an event for THE GODFATHER

Reportedly, Robert Evans hated Nino Rota's original score and sought to replace it with one by Henry Mancini. Coppola threatened to quit over this, until Evans backed down.

During filming, Coppola complained about the station wagon that picked him up, so he and Robert Evans made a bet that if the film made $50 million, Paramount Pictures would spring for a new car. As the film's grosses climbed, Coppola and George Lucas went car shopping, and bought a Mercedes Benz 600 stretch limousine, instructing the salesman to send the bill to Paramount. The car appears in the opening scene of AMERICAN GRAFFITI (1973).

A Hollywood Reporter feature article on 7 April 1972 announced Evans' plans to personally supervise the production of four foreign-language versions of THE GODFATHER, which would be dubbed outside the U.S. A subsequent news item reported that French director Louis Malle was in charge of dubbing the French-language version, and that the actors were to be paid twice the normal amount for dubbing because of the importance of the film.

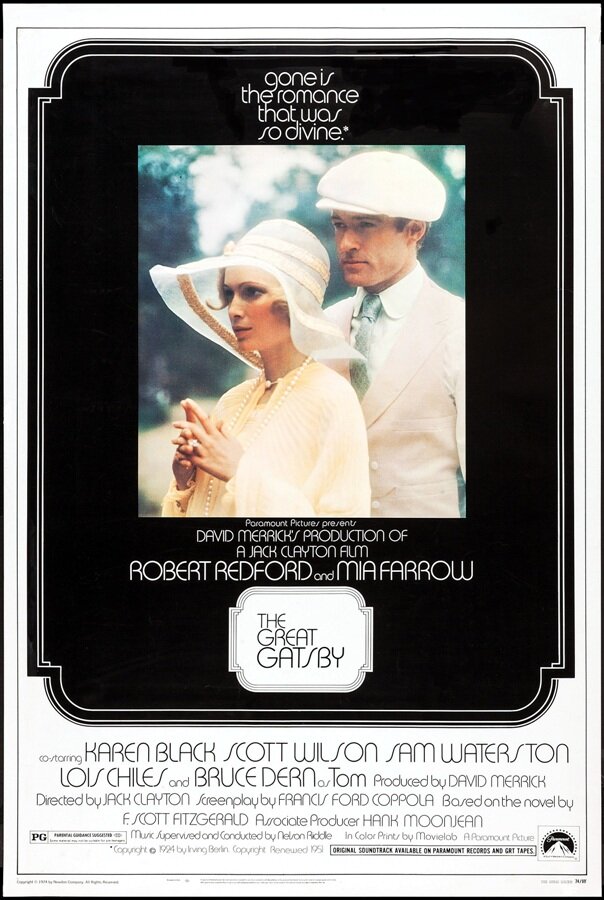

Pre-production for THE GREAT GATSBY began in mid-1971. Robert Evans, Paramount’s head of production at the time, and eventually the co-Executive Producer on the film, was planning to turn the property into a vehicle for his then wife, Ali MacGraw, and Robert Redford. Broadway impresario David Merrick, who owned the film rights, would produce the picture. Francis Ford Coppola had been hired early on to write the film's screenplay, although author Truman Capote had drafted an earlier version of the script that was abandoned. Although principal photography was to have started in July 1972, Paramount announced that it was delaying the production until May 1973. The picture ultimately began production on 11 June 1973.

Because of the production delays on THE GREAT GATSBY, Ali MacGraw agreed to star in THE GETAWAY (1972). During production of that film, MacGraw fell in love with co-star Steve McQueen and left Evans for him. MacGraw and Evans separated in late 1972 and divorced some months later. As reported in a 1 November 1972 Variety news item, MacGraw's name had recently been removed from consideration for the role of “Daisy.” As Evans stated in an 18 November 1996 People magazine interview, "I bought The Great Gatsby as a wedding gift to my then wife Ali MacGraw, and I took it away as a divorce gift."

According to Evans, the final five names considered for the role of Daisy Buchanan were Mia Farrow, Faye Dunaway, Candice Bergen, Katharine Ross, and Lois Chiles. On 18 December 1972, Mia Farrow was announced in Hollywood trade papers as the final choice to portray Daisy. Chiles was given the smaller role of “Jordan Baker.” No pre-production news items mentioned any actor other than Redford for the role of Gatsby. However, in a Los Angeles Herald-Examiner article on 6 May 1975, Evans stated that he and THE GREAT GATSBY director Jack Clayton had actually wanted Jack Nicholson for the role.

In his later memoirs, Robert Evans stated that Warren Beatty was approached to play Gatsby. He wanted to direct the film, and suggested Evans play the role himself. Jack Nicholson didn't believe Ali MacGraw was appropriate for Daisy. Steve McQueen was also considered and rejected for the role.

Even before principal photography began, there was an extensive publicity campaign for the film. Both Time and Newsweek published lengthy cover stories about the production. In the 18 March 1974 Time article, entitled "Ready or Not, Here Comes Gatsby," Robert Evans was quoted as saying "The making of a blockbuster is the newest art form of the 20th century." Paramount created a special merchandising division for the film. A December 1973 Vogue magazine article on the picture, which was quoted in the pressbook, reported that THE GREAT GATSBY "caused the greatest pre-production excitement since GONE WITH THE WIND.”

The picture was ranked eighth in the list of top moneymaking films of 1974, taking in $14,200,000 in the North American box office. The production received two Academy Award nominations, and was awarded the Oscar in both categories: Costume design (Theoni V. Aldredge) and Adapted Score (Nelson Riddle).

Just a few weeks after the premiere of THE GODFATHER, a 7 April 1972 Hollywood Reporter article announced that Robert Evans would produce, but Francis Ford Coppola would not direct, a sequel to THE GODFATHER, then tentatively entitled “Don Michael,” because Coppola would be busy with other projects. Although Robert Evans was credited as executive producer on THE GODFATHER PART II, one of Francis Ford Coppola's conditions on returning to direct was that Evans have no direct involvement whatsoever with the film, as they had frequently clashed while making the first film. Evans seems to have honored this request, as there is little record of any decisions he made regarding the production. Coppola himself was the producer of the film.

The multiple-Academy Award-winning sequel was co-written by Coppola and Mario Puzo. The second film, which was partially original and partially based on portions of Puzo's novel that were not in the film THE GODFATHER, featured many of the principal actors from the first film, including Al Pacino, Diane Keaton, John Cazale, Robert Duvall, and Talia Shire, and followed Michael Corleone's life as the head of the Corleone family. The film also included lengthy flashback segments devoted to the early life of Don Vito, who was played as a young man by Robert De Niro.

CHINATOWN was the first film personally produced by Paramount studio production head Robert Evans, and marked the first time that he received an onscreen producer credit. Director Roman Polanski had been planning to make a film with Jack Nicholson, but hadn't found the right property yet. He actively pursued the script for CHINATOWN when he learned about it. As luck would have it, Polanski was also Evans' first choice for director, as he wanted a European vision of the United States, which he felt would be darker, and a little more cynical. Evans also knew that Polanski was coming off two major flops, MACBETH (1971) and the lesser known WHAT? (1972), and that he would be very keen to impress, and would make every effort to ensure that CHINATOWN was a hit.

Despite lobbying Evans and Nicholson for the chance to direct the film, when he finally landed the job Polanski started having second thoughts. The idea of returning to Los Angeles, where his wife Sharon Tate had been brutally murdered four years earlier, was difficult for him.

Evans wanted Jane Fonda for the part of “Evelyn Mulwray,” while Polanski insisted upon Faye Dunaway. Dunaway was Polanski's vision for the 1930s character since his mother used to have pencil eyebrows and wore red lipstick in the shape of Cupid's bow, as depicted in Dunaway's make-up.

Polanski wanted William A. Fraker as his cinematographer, having successfully collaborated with him on ROSEMARY’S BABY (1968). This idea was blocked by Evans, who felt that the pairing of the two would create too powerful a bond, making his life as a producer more difficult. Evans and Polanski agreed that cinematographer Stanley Cortez would be hired, but he was fired by Polanski soon after production began. His classical style did not match the naturalistic style Polanski wanted for the film, and he proved to be too time consuming. Polanski had to find a replacement in only a few days and chose John A. Alonzo.

According to Polanski's autobiography, he was outraged when he got the first batch of dailies back from the lab. Due to the success of THE GODFATHER, Robert Evans had ordered the lab to give CHINATOWN the same reddish look. Polanski demanded that the film be corrected.

Roman Polanski chose classical composer Phillip Lambro to compose the film’s score. For the first screening, Polanski took his old friend, composer Bronislau Kaper. Robert Evans afterwards asked Kaper what he thought of the picture, to which Kaper replied, "It's a great film, but you have to change the music." Following that unsuccessful preview, Evans insisted that Jerry Goldsmith be brought onto the project to compose a new score. Goldsmith's score, highlighted by its haunting trumpet solo, has been celebrated by both contemporary and modern critics as one of the best, most recognizable film scores of all time, and frequently has been included in concert repertoires devoted to film music. At a 1995 Los Angeles Film Critics program in honor of CHINATOWN, Goldsmith, screenwriter Robert Towne, and others revealed that time constrictions forced Goldsmith to finish the score in eight to ten days.

Critics had high praise for the film, citing not only the direction, screenplay and acting, but also Richard Sylbert's art direction and Anthea Sylbert's period costumes. Faye Dunaway's costumes and 1930s look received particular attention in fashion magazines, such as W, which devoted a 28 December 1973 multipage feature to her clothes. According to studio publicity notes, the production used sixty-five vintage cars, highlighted by “Evelyn's” cream-colored Packard convertible. The overall look of the film began with Evans, who wanted the picture to emulate a classic Hollywood film noir.

A 20 May 1974 Publishers Weekly news item announced that filming rights to William Goldman’s novel, MARATHON MAN, were sold to Paramount Pictures, with Robert Evans and Sidney Beckerman set to produce, and Goldman contracted to write the screenplay. Goldman was to receive $500,000 for the rights and his writing services, as well as “a substantial participation in the profits.”

Director John Schlesinger envisioned a cast of Al Pacino, Julie Christie, and Sir Laurence Olivier. Pacino has said that the only actress he had ever wanted to work with was Christie, who he claimed was "the most poetic of actresses". Robert Evans, who disparaged Pacino as "The Midget" when Francis Ford Coppola wanted him for THE GODFATHER, and had thought of firing him during the early shooting of that now-classic movie, vetoed Pacino for the lead. Instead, Evans insisted on the casting of the even shorter Dustin Hoffman. Christie, who was notoriously finicky about accepting roles, even in prestigious, sure-fire material, turned down the female lead, which was then taken by Marthe Keller.

Of his dream cast, Schlesinger only got Olivier. But according to Robert Evans, in an all-too-rare occurrence, all of his first choices for the film's leads-- Hoffman, Olivier, Roy Scheider, William Devane, and Keller--were cast in the roles for which he envisioned them.

Robert Evans was particularly set upon getting Sir Laurence Olivier to play the role of “Szell.” However, because Olivier at the time was riddled with cancer, he was uninsurable, so Paramount refused to use him. In desperation, Evans called his friends Merle Oberon and David Niven to arrange a meeting with the House of Lords (the upper body of the British parliament). There, he urged them to put pressure on Lloyd's of London to insure Britain's greatest living actor. The ploy succeeded, and a frail Olivier started working on the film. In the end, not only did Olivier net an Oscar nomination as Best Actor in a Supporting Role, but his cancer also went into remission. Olivier lived on for another thirteen years.

Although Goldman had written for him in ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN, Dustin Hoffman was not particularly a fan of Goldman's original novel for MARATHON MAN. Hoffman took the lead role so that he could work with John Schlesinger again (the two had previously collaborated on MIDNIGHT COWBOY (1969)). He had also heard that Al Pacino was interested in the role and wanted to beat him to it.

Hoffman lost fifteen pounds for his role. He ran up to four miles a day to get into shape for playing the part. He would never come into a scene and fake the breathing. According to Evans, Hoffman "would run, just for a take, he would run for a half-mile so he came into the scene, he'd actually be out of breath."

Outtakes from the film reveal that several actors enjoyed imitating the unique speech patterns of Robert Evans. Two decades later, Dustin Hoffman used such an imitation for his performance in WAG THE DOG (1997).

Michael Small's score for the film was released by Film Score Monthly in 2010.

For his production of the 1977 thriller BLACK SUNDAY, producer Robert Evans drew upon some talent with whom he had previously worked. Cast members Marthe Keller and Fritz Weaver had also appeared in MARATHON MAN. Cinematographer John A. Alonzo had shot CHINATOWN.

Director John Frankenheimer was able to secure permission from Goodyear to use its blimp in the film because of his relationship with the company's public relations department from making GRAND PRIX (1966). Reportedly, Frankenheimer also stated that he persuaded Goodyear to let him used the blimp because if they refused, the production would rent a large blimp from Germany, paint it silver-and-black, and people would think it was a Goodyear blimp anyway. Frankenheimer had to promise that the blimp itself would not kill anybody in the film - for example, that no one would be torn up in its propellers. In addition, the pilot was changed in the script from a Goodyear employee to a freelance pilot only hired by Goodyear.

Miami Dolphins owner Joe Robbie got the NFL to allow extensive filming at a real Super Bowl game and the use of copyrighted team names and logos. Additional footage of the stampede at the game was shot at the Orange Bowl after the game with thousands of extras provided for free by The United Way. In exchange for providing the extras, Frankenheimer agreed to direct a short film for them with star Robert Shaw narrating it.

Before shooting began, Robert Shaw contacted his old friend Alan Bates to see what John Frankenheimer was like. Bates, who had worked with Frankenheimer on THE FIXER (1968), told him they would get on fine as they were both "mad".

John Williams’ score for the film was released by Film Score Monthly in 2010.

Producer Robert Evans was eager to film another romance after shepherding the box-office hit LOVE STORY (1970) as production executive at Paramount Pictures. He developed the concept for PLAYERS with screenwriter-executive producer Arnold Schulman and associate producer Tommy Cook. Cook, who transitioned from his early days as an actor and junior tennis champion into an organizer of celebrity tennis tournaments, brought the story idea to Evans.

LOVE STORY also inspired Evans to reteam with the film’s co-star, Ali MacGraw, and to hire Anthony Harvey as director. Harvey was originally signed to direct LOVE STORY, but withdrew from the project. Before departing, Evans recalled that Harvey was responsible for eliciting a memorable screen test from MacGraw. Evans and MacGraw had been married before she left him and married Steve McQueen in 1973. MacGraw’s divorce from McQueen became final shortly after production on PLAYERS began.

The unique casting process involved selecting professional tennis athletes for lead and feature roles, such as Dean-Paul Martin, Guillermo Vilas, and Pancho Gonzalez. With the exception of Martin, players appeared as themselves in the film. Martin, the son of entertainer Dean Martin, was a member of the pro-tennis team The Phoenix Racquets, and had been coached during childhood by Tommy Cook, who suggested him for the role of “Chris Christensen.” Although Martin was disinterested in an acting career, a story set within the world of contemporary tennis was a rare subject for films, and he was persuaded to audition. Martin consulted with psychiatrist Lee Baumel, rather than a drama coach, to practice releasing emotions in preparation for his feature film debut. Actor Tony Franciosa was enlisted to advise the newcomer about camera technique, but was not credited onscreen. Recognizing Martin’s potential, Robert Evans signed him to a six-picture deal.

Other professional tennis players agreed to appear in the film under certain conditions. For example, tennis champion Ilie Nastase did not want to lose the Wimbledon semifinal, as written in the script, so the filmmakers found a compromise whereby Nastase suffers a leg injury in the scene and must default to Martin.

Principal photography began 3 July 1978 at the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club in Wimbledon, England, home to one of the four Grand Slam tennis championships. In an exceptional arrangement for the traditional All England Club, the filmmakers were permitted to shoot crowd, locker room, and certain on-court scenes during the fortnight tournament. Prior to the start of the ladies’ final between opponents Martina Navratilova and Chris Evert, the production took advantage of the real setting and filmed Martin and Vilas walking onto Centre Court and bowing to Princess Margaret and the Duchess of Kent in the Royal Box.

The week after the tournament, the five-set match between Martin and Vilas was staged on Centre Court and included the participation of actual Wimbledon officials, such as tournament umpire Herbert Syndercombe, referee Fred Hoyles, and British Broadcasting Corporation commentator, Dan Maskell. The Wimbledon rental fee was $35,000. Additional locations included areas in and around Cuernavaca, Mexico; Caesars Palace Casino in Las Vegas; and the LAC II yacht in Monte Carlo, Monaco. The production also used the Los Angeles Tennis Club. When Harvey fractured his knee during the final weeks of shooting in Las Vegas, Robert Evans took over directing duties.

A conflict between co-screenwriter and executive producer Arnold Schulman and Robert Evans became evident in the wake of the picture’s release to poor reviews. Soon after the 8 June 1979 opening, Schulman purchased full-page advertisements in Daily Variety and the Hollywood Reporter, which quoted some of the negative comments about his screenplay and included a claim that Evans rewrote his script “line by line.” Later, Schulman filed a multi-million dollar lawsuit against Evans and Paramount Pictures, for breach of contract, and against Harper & Row Publishing Inc. for neglecting to publish a novel based on the film. The outcome of the litigation in not known.

Jerry Goldsmith, who had scored CHINATOWN for Evans, provided the film’s score. It was released by Intrada in 2010. PLAYERS grossed $4.9 million at the box office, a far cry from LOVE STORY’s $106 million.

URBAN COWBOY originated from a 1978 Esquire article by Aaron Latham titled “The Ballad of the Urban Cowboy: America's Search for True Grit.” The article celebrated Gilley's, a nightclub in Pasadena, TX, which claimed to be “the biggest honky-tonk in America,” and was “the size of two football fields,” with the capacity to accommodate roughly 8,000 patrons. Latham portrayed the establishment as the haunt of the contemporary Texas cowboy, who most likely worked at a chemical plant instead of a ranch. Latham stated that “the cowboy, the most enduring symbol of our country,” needed to be reinvented, generation after generation, by people of the American West.

An 8 November 1978 Daily Variety news item announced that music industry manager Irving Azoff, had purchased rights to Latham’s story and would co-produce a feature film adaptation with Robert Evans. Azoff reportedly paid $250,000 to Esquire and Gilley’s owner and musician, Mickey Gilley, for the rights.

Michelle Pfeiffer auditioned for the role of “Sissy” and was co-producer Robert Evans' preferred choice. After Debra Winger was hired, Robert Evans sent her back from location because he did not think she was attractive enough for the lead. It was only at the insistence of director James Bridges that she continued in the role.

Originally slated to shoot in June 1979, the production was delayed three weeks when John Travolta's dog bit his lip. Travolta had been practicing daily on a mechanical bull set up in his Santa Barbara, CA, home specifically for his role in the film. Shooting began on location 2 July 1979 outside of Houston. Shortly after, it was rumored that Travolta's erratic behavior on set might halt the production, according to some Paramount executives. Travolta was allegedly concerned about his career after the box-office failure of his latest film, MOMENT BY MOMENT (1978). Robert Evans denied the rumors, admitting only that the film was over budget because of the late start in shooting. Ultimately, the film cost $13 million, $2 million more than initially budgeted.

The production featured a closed set with many security precautions implemented to protect John Travolta from the media. Travolta had mandated no publicity during filming and was at the time known to have become reclusive. The film garnered much negative publicity during principal photography anyway, with Robert Evans once exclaiming "the press relations on this film stink and there's nothing I can do about it."

The film’s soundtrack, with songs performed by Bonnie Raitt, Boz Scaggs, and the Charlie Daniels Band among others, fulfilled Irving Azoff's commercial hopes and was the top-seller for Warner/Elektra/Atlantic Corp., earning $23 million in 1980 and engendering a follow-up album. Music coordinator Becky Shargo and writer Aaron Latham filed against Azoff in separate suits, both for breach of contract, claiming they should have received royalties from the album. The film itself was a commercial success, grossing $47 million.

The genesis of POPEYE began with actor Dustin Hoffman’s desire to do a kid-friendly movie. He approached producer Robert Evans with a project about clowns, and another about Dracula, but Evans did not share his enthusiasm. Instead, Evans noticed in the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers that the Popeye theme song earned $75,000 a year in royalties. The popularity of the character around the world made him think that a Popeye musical would have commercial potential.

Around the same time, Paramount lost a bidding war with Columbia for the screen rights to the musical “Annie”. Evans held an executive meeting in which he asked about comic strip characters that they had the rights to, that could also be used to create a movie musical, and one attendee recommended Popeye. Evans bought the film rights from King Features Syndicate after a few months of negotiations.

Evans considered the following directors for the project: Hal Ashby, Arthur Penn, Richard Attenborough, Louis Malle, Jerry Lewis, and Mike Nichols. Screenwriter Jules Feiffer said he ruled out Jerry Lewis, and after the other directors had said no, Robert Altman said he wanted to make the film, loved the screenplay, and would not change a word. "I laughed when Evans reported this to me," Feiffer wrote in his memoir. "I was a friend of Altman's and a fan. As a fan I knew what was coming. Altman didn't believe in scripts except as a necessary evil to get films financed. He didn't much believe in words, he didn't care if you heard the dialogue or not. And he didn't believe in story. But I could imagine no one better to give credibility to Segar's outlandish creations on-screen."

Dustin Hoffman and Lily Tomlin had been cast as leads. Hoffman began dance lessons to prepare for his role. But, in time, Hoffman disagreed with Feiffer’s interpretation of the character and suggested that Evans fire the screenwriter. According to Feiffer, Evans kept the script and dropped Hoffman from the project. “A first in Hollywood history,” Feiffer said. After actor-comedian Robin Williams was signed to replace Hoffman, Lily Tomlin withdrew from the project. As a result of losing its star power, the project lapsed into limbo.

Actress Gilda Radnor was considered by Evans for the role of “Olive Oyl,” but opted to return to the cast of “Saturday Night Live”. Radnor stated that she would reconsider the part if the shooting schedule began in March or April 1980. However, when the timing could not be worked out, Radnor passed on the project. Ultimately, Robert Altman’s preferred choice of Shelley Duvall was signed for the part.

Williams began lifting weights and dyed his hair red for his role as “Popeye.” Williams also researched his part by watching the 1930s Max Fleischer animated cartoons voiced by Jack Mercer, and later, Mercer’s work in Hanna-Barbera’s Popeye animation. The make-up appliances for Williams's fake forearms were not ready when filming began, so in early shots, Popeye wears a long-sleeved raincoat to hide his normal-sized arms. Filmmakers found it necessary to re-record some of Williams’ muttered “Popeye” dialogue just prior to the movie’s release to make it more comprehensible to audiences.

Actor Paul L. Smith, cast as “Bluto,” grew back his bushy beard, and bulked up to three hundred and fifty pounds to play the role. Back in 1977, Evans had suggested that choreographer Patricia Birch and executive producer Richard Sylbert would be additional hires, but others were eventually hired to fill those positions.

Robert Evans, Jules Feiffer, and Robert Altman on the set of POPEYE

Paramount Pictures chairman Barry Diller brokered a deal between his company and Walt Disney Productions to co-finance and co-distribute the picture, and also DRAGONSLAYER (1981). Paramount agreed to handle domestic distribution, while it was felt that Disney, with its greater overseas potential, would be responsible for the international market. It was the first time that Disney partnered to distribute a film, while Paramount had entered into a joint distribution deal once before with Universal Pictures to release SORCERER (1977).

Robert Altman and production designer Wolf Kroeger scouted U. S. locations including Catalina Island, CA, Florida, and Hawaii, before settling on Anchor Bay, Malta. The area, with its distinctive “horseshoe-shaped cove,” afforded filmmakers much privacy on the thinly populated northwest section of the island. During the summer of 1979, the crew built a two hundred-foot ferryboat to use as a breakwater in the bay, access roads and a model built to scale. Construction on the village began in September 1979 with 165 crew members including draftsmen, scenic painters, carpenters, electricians, plasterers, welders, and sculptors. Hand-split cedar shingles were imported from British Columbia, and lumber was shipped from Austrian forests.

Crew members built an underwater tank, barges, and a seaport to represent the fictitious town of Sweethaven, which consisted of churches, houses, restaurants, and bars along a stretch of almost three blocks in a cove twenty miles from the Maltese capital of Valletta. Nineteen structures made up the village including the four-bedroom Oyl house, the Rough House Café and its short-order kitchen, and a working sawmill. In addition, the upper cabin of the ferryboat became the town’s gambling casino, and a half-submerged frigate in the bay was used as the Commodore’s headquarters.

An all-around danceable, swimmable, walking and running shoe was designed and constructed for cast members by a London manufacturer of theatrical footwear named Anello and Davide. Shoes were made of leather and rubber, and padded with cork to suggest exaggerated toes and bulging heels. Each shoe was about twice the length of an actor’s regular shoe size, and the company prepared eighteen pairs for the production, while the bulk of the footwear was manufactured in the plaster shop on the set.

A moderate success, POPEYE made $61 million worldwide during its release. Nevertheless, Paramount filed a lawsuit after director Altman went over budget on the film, alleging that Altman had agreed to repay ten-nineteenths of any amount that exceeded the budget, excluding interest, up to $250 thousand. The movie cost more than $22.7 million. Paramount asked for $250 thousand in damages from Altman, whose salary on the film was $600 thousand. Altman refused to honor the agreement, according to the suit. The outcome of the dispute has not been determined.

Everyone tried to dissuade Robert Altman from working with composer/songwriter Harry Nilsson, saying that he would be constantly drunk. Only Robin Williams supported Altman in this decision. As it turned out, Altman found Nilsson to be delightful to work with. Nilsson’s score and songs, with some additional music by Tom Pierson, were released on a Boardwalk LP. An expanded edition was issued on CD by Varese Sarabande in 2017.

The outdoor Sweethaven set was saved from destruction by lifelong Maltese resident, Lino Cassar, a dedicated film buff and coordinator for area filming. Cassar battled Maltese officials to preserve the village, and eventually brought his case before the country’s prime minister. As a result, the site remains a popular tourist destination, where visitors can walk through nineteen buildings including a restaurant with menu items like spinach soup and Wimpy hamburgers.

During the production of POPEYE, Robert Evans was arrested for trying to buy cocaine. He entered a guilty plea to a misdemeanor in Federal court after being arrested after engineering a large cocaine buy with his brother Charles. As part of his plea bargain, he filmed an anti-drug TV commercial. The alleged drug dealing, which Evans subsequently denied (the misdemeanor was later wiped from his record), came out of his own involvement with the drug. He told the Philadelphia Inquirer in a 1994 interview, "Bob 'Cocaine' Evans is how I'll be known to my grave". He argued that he never should have been convicted of Federal selling and distribution charges, as he was only a user.

THE COTTON CLUB interweaves two narratives, following the lives of Harlem musician “Dixie Dwyer,” a white coronet player of Irish descent, and “Sandman Williams,” an African-American tap dancer. While Dixie and Sandman’s stories are generally depicted separately, events often overlap, particularly at the Cotton Club. Musical numbers are intercut with the film’s action, blurring the distinction between performance and “real” occurrences in the movie. The picture also includes fictional representations of historical figures, such as actress Gloria Swanson (Diane Venora) and gangsters Charles “Lucky” Luciano (Joe Dallesandro), Dutch Schultz (James Remar), and Owney Madden (Bob Hoskins).

In December 1980, producer Robert Evans acquired film rights to James Haskins’s book The Cotton Club: A Pictorial and Social History of the Most Famous Symbol of the Jazz Era. At that time, Evans was known for his success as head of production at Paramount Pictures, where he pulled the studio out of financial decline with blockbusters including Francis Ford Coppola’s THE GODFATHER (1972) and Roman Polanski’s CHINATOWN (1974). After CHINATOWN, Evans negotiated a deal with Paramount in which he maintained his executive title while also developing side projects and financing them as an independent producer.

Evans was first introduced to Haskins’s book in 1977, when literary agent George Weiser brought the story to his attention with plans to make a Broadway musical. Seeing the picture as an updated GONE WITH THE WIND, which could integrate African-American actors into Hollywood filmmaking and explore the history of race relations in the U.S., Evans believed THE COTTON CLUB project was vital to promoting cultural diversity and spent $475,000 of his own money to acquire screen rights. Although Evans secured private financing for the picture as of 12 December 1980, Paramount was given the option to take over as producer, but the studio was awaiting returns from their recent Evans investment, POPEYE, which was set to open that day. In the meantime, POPEYE director Robert Altman was hired to direct THE COTTON CLUB.

Five months later, in April 1981, Evans announced plans to break ties with Paramount and produce the film on his own, with an $18 million budget supplied by an unnamed Swiss investment group. Working independently, Evans hoped to retain ownership of the picture’s negative, which would give him control over its copyright, rentals, and television rights, but his plan did not appeal to investors, who wished to share in the profits. With the modest box-office results of POPEYE, as well as legal troubles resulting from a cocaine trafficking arrest, and the loss of millions of dollars in poor stock-market investments, Evans believed THE COTTON CLUB was his best opportunity to resurrect his career.

In an attempt to replicate the success of THE GODFATHER, Evans hired writer Mario Puzo to adapt Haskins’s book. The deal was announced in a 17 September 1981 New York Times article, which noted that production was delayed because Evans spent the past year working on an anti-drug television campaign to expunge his criminal record. During that time, THE COTTON CLUB budget increased to approximately $20 million, and Robert Altman left the project. When Evans hired Puzo for $1 million, he was desperate to find greater sources of financing, and actress Melissa Prophet, who had a role in Evans’s 1979 film PLAYERS, introduced him to Saudi Arabian billionaire arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi. Evans was negotiating a distribution deal with Paramount at that time, and Khashoggi agreed to supply an initial $2.5 million if the studio matched his investment as a co-financier. When Paramount complied, Khashoggi increased his commitment to $12 million and Paramount balked at the unexpected budget hike. The deal never came to fruition and Evans returned Khashoggi’s $2.5 million.

When Paramount dropped out, Evans sought the services of Orion Pictures, which was in the business of marketing and distributing films rather than producing them, meaning that Evans would need to raise more production money and find a studio in which to shoot the film, causing further delays and adding to the already bloated budget.

On 4 March 1982, the Hollywood Reporter announced that GODFATHER star Al Pacino was cast in the role of “Dixie Dwyer,” but he was replaced by Sylvester Stallone two months later, when it was also reported that Evans had taken over as director. The film would have marked Evans’s directorial debut. Stallone was guaranteed a $2 million salary as well as a 25% cut of any money the production saved if it was completed under budget. Several days after settling Stallone’s contract, Evans went to the 1981 Cannes Film Festival, hoping to secure financing from foreign theater chains, and obtained $8 million in guarantees from the Producers Sales Organization (PSO). However, the deal stipulated that Evans could not have access to the money until the film was completed, or was subsidized by a completion bond.

Without evidence of immediate financial backing, Evans was unable to gain investor confidence and sought funding from brothers Ed and Fred Doumani, who were leading property and casino owners in Las Vegas. Although the men were facing a corruption review by the Nevada Gaming Control Board, they agreed to finance THE COTTON CLUB with a partner, businessman Victor L. Sayyah, in return for 50% ownership of the film. Evans supplied collateral by mortgaging his Beverly Hills mansion, liquidating his savings, and selling his stock in Paramount parent company, Gulf + Western. Neither the Doumanis nor Sayyah are credited onscreen.

In addition, millionaire entertainment promoter Roy Radin was brought in as an investor by Evans’s then-girlfriend, Karen Greenberger (a.k.a. Elaine “Lanie” Jacobs), a cocaine dealer with ties to the Latin American drug trade. The deal mandated that Evans and Radin establish a production company in which each would own 45% of the film with the remaining 10% split between two other parties. Radin offered Greenberger a $50,000 finder's fee for her efforts, which she found unsatisfactory. However, the deal ended when the 33-year-old Radin was murdered during pre-production.

By June 1982, Harrison Ford was cast to replace Sylvester Stallone, but in September 1982 it was reported that Evans was ready to start production in February 1983 with Richard Gere in the leading role. Catherine Denueve was under consideration to play “Vero Cicero,” and the filmmaker was in the process of casting 150 black actors. Although Richard Pryor was Evans’ first choice for “Sandman Williams,” the budget could not accommodate his salary demands. Gregory Hines was ultimately cast. Diane Lane was then cast as Vero Cicero.

With financing secured, Evans hired Francis Ford Coppola to rewrite Puzo’s screenplay, which had already gone through approximately sixty drafts. Evans and Coppola were notorious adversaries from their work on THE GODFATHER, but Evans believed the filmmaker had a better chance at making the project a success, and soon asked Coppola to direct. Coppola was motivated to take over THE COTTON CLUB because he was at a standstill in his career after the commercial failure of ONE FROM THE HEART (1982), which forced his company, Zoetrope Studios, into bankruptcy. Coppola agreed with Evans that THE COTTON CLUB would be a blockbuster, and its success could resurrect their credibility.

Coppola’s script was nearly finished by early August 1983 and principal photography was scheduled to begin in New York City on 22 August 1983. Although Coppola promised the screenplay would be ready in time for production, Evans hired Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist William Kennedy to guarantee a completed script. Kennedy spent eight days writing a “rehearsal script” that was used by the cast in the three weeks leading up to the start of production. After filming began at Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens, NY, Kennedy and Coppola created twelve additional drafts, and the actors were encouraged to submit notes, leaving the shooting script a work-in-progress.

Along with spontaneous changes in the narrative, upon being appointed director, Coppola added to the budgetary woes by firing en masse the film crew Evans had assembled (in some cases requiring large payoffs). Other firings included unit production manager David Golden, executive producer Dyson Lovell, music consultant Jerry Wexler, and arranger Ralph Burns. Coppola hired his own crew members, including a music arranger who commuted via Concorde between the shoot in New York and a regular engagement in Switzerland.

In addition, Coppola walked off set the week of 3 October 1983, causing filming to stop for several days. According to one report, Coppola objected to his contract, which stipulated that he be paid $3 million upfront with an additional $1 million if the film was finished on time and within its $18-$20 million budget. Evans retained the option to deduct Coppola’s wages if the film’s cost exceeded $20 million. Seven weeks into production, the budget already reached $28 million, and Coppola refused to continue until he was guaranteed more money upfront. But another report claimed that Coppola was not paid in full because he did not finish the script. At one point relations were so strained between Coppola and Evans that Coppola had Evans banned from the set. Evans agreed to Coppola’s terms so filming could resume. Although principal photography was completed in 1983, the first-unit crew and cast returned to New York City in mid-March 1984 for additional location shooting.

Production designer Richard Sylbert claimed that he told Robert Evans not to hire Coppola because "he resents being in the commercial, narrative, Hollywood movie business". Coppola claimed that he had letters from Sylbert that asked him to work on the film because Evans was crazy. The director also said that "Evans set the tone for the level of extravagance long before I got there".

The film’s soaring budget resulted in several lawsuits and conflicts between Evans, Coppola, and their investors. When the cost exceeded $20 million, the Doumani brothers convinced distributor Orion Pictures to advance the production an additional $15 million, on condition that Evans step down as producer. Although Evans objected to being replaced by Ed Doumani, he agreed to the deal because he believed investor Victor L. Sayyah was supportive of the pact. In addition, the Doumanis hired a noted gangster, Joseph Cusumano, to intimidate Evans into giving up his share of the partnership. Cusumano is credited onscreen as line producer. When Evans discovered that Sayyah was not behind the Doumani arrangement, he filed a restraining order against Ed Doumani to prevent him from taking over the picture.

On 10 June 1984, Sayyah filed a lawsuit against the Doumani brothers, their attorney, David Hurwitz, Orion Pictures, Robert Evans, and PSO, alleging fraud, conspiracy, and breach of contract. Sayyah claimed it would be impossible for him to recoup his $5 million investment because the film’s budget escalated from $20 to $58 million during production, making it unlikely that the picture would make a profit. Sayyah also contended that Orion’s $15 million loan was unnecessary, and may have been orchestrated to increase the budget so he would be edged out of a return on his investment. Complaints were also made against the Doumanis, who allegedly pushed Evans into a state of vexation on purpose, so he would lose control of the project. The Canadian Globe and Mail estimated the budget could have been as high as $67 million, but the filmmakers were not able to confirm an exact figure.

Ten days after Sayyah filed his lawsuit, a court ruling restored Evans’s authority. However, line producer Barrie M. Osborne was granted full control over post-production. Osborne was a close confidante of Coppola, and the ruling was a greater victory for Coppola than for Evans, who was effectively denied participation in the final cut. Evans received a flat fee and producer credit, but was stripped of creative control. The court also forbade the warring parties to file additional lawsuits about the film without approval from the judge.

Despite generally positive reviews, the picture did not fare well at the box-office, grossing $2.9 million its opening weekend on 808 screens. Orion experienced unusually high levels of trading on Wall Street after the film’s release. The transactions reflected a common anxiety that the studio would suffer financially from THE COTTON CLUB. Orion tried to reassure traders with a press statement, claiming its investment in the movie was “fixed and limited.” The film’s ultimate box office take was an anemic $26 million. John Barry’s score claimed only two tracks on the song CD released by Geffen Records.

Los Angeles County sheriff’s investigators had all but given up their investigation of Roy Radin’s murder, but a break came in 1987 when they met William Rider, the brother-in-law and onetime security chief for Larry Flynt, publisher of Hustler magazine. Rider told them that William Mentzer and Alex Marti had admitted during a poker game that they killed Radin. Mentzer, Marti and Robert Lowe were bodyguards for Flynt at the time they met Karen Greenberger.

The arrests of the four came after a secret taping by Rider of a conversation in which Lowe said the Radin killing had been paid for by Greenberger and film producer Robert Evans, and was contracted for because Greenberger feared she was being cut out of a producer’s role – and profits – in the movie. The ensuing trial for the murder of Roy Radin became known as “The Cotton Club Trial.”

Although Evans was not charged in the case, on the advice of his attorney Robert Shapiro, Evans refused to testify during a May 1989 preliminary hearing, invoking the Fifth Amendment to avoid incriminating himself. Contract killers William Mentzer and Alex Marti were convicted of first degree murder, for shooting Radin multiple times in the head and using dynamite to make identification by authorities more challenging. Karen Greenberger testified during her 1991 trial that Evans was not involved in the murder. She also claimed during her trial that she had been Evans' lover. Greenberger and Lowe were convicted of second-degree murder and kidnapping and received life sentences.

For many years after CHINATOWN, there were attempts by Jack Nicholson, Robert Towne and Robert Evans to follow-up the story with a sequel. The sequel, THE TWO JAKES, would pick up the story of “Jake Gittes” in 1948. Evans, who produced CHINATOWN, was slated to continue as producer for the sequel and had negotiated for Jack Nicholson to return to the role of Jake Gittes and for Dustin Hoffman to play “Jake Berman,” with the intention of beginning production in 1977. CHINATOWN director Roman Polanski was unable to work in the United States after taking up residence in France to avoid a California jail sentence that would have resulted from his guilty plea to a charge of having unlawful sex with a minor in February 1978, and screenwriter Robert Towne replaced him as director of the sequel.

By 1985, the film project had still not moved forward, and Evans, who began his film career as an actor, was contracted to play the role of Berman, as the part was written for him by Towne, a longtime friend and colleague. Towne, Evans and Nicholson jump-started the project by forming the independent production companies T.E.N. Productions, based on an acronym of their names Towne-Evans-Nicholson, and Two Jakes Productions, to collectively profit from the venture.

In return for the trio sacrificing their salaries, Paramount agreed to a budget of $12 to $13 million and a cap of $6 million on its standard thirty percent distribution fee, which would have enabled Towne, Evans and Nicholson to share profits after Paramount recouped production costs and the distribution cap was met. Due to this arrangement, THE TWO JAKES was technically an independent production. Paramount consented to fund the entire project because they were entitled to independent production incentives, as they would in a negative pick-up deal, which allowed them to pay for the production after shooting and save up to 15% in overhead costs.

Evans announced his intent to play Berman as part of the deal, and various contemporary sources, including Los Angeles Magazine, speculated that this reflected an attempt to redeem his reputation after much publicized controversies surrounding THE COTTON CLUB, including the murder of one of that film’s financers, Roy Radin, and Evans’s rumored problems with cocaine addiction. Kelly McGillis, Cathy Moriarty, Dennis Hooper and Harvey Keitel were also cast (although only Keitel appeared in the final film), sets were under construction and props, such as classic cars, were purchased and prepared for production to begin.

Robert Evans underwent major plastic surgery before the film began, reportedly bringing pictures of cats with him to get the look he wanted. Nicholson and Towne were horrified when they saw the results, because Evans had become unrecognizable. After shooting several test scenes in April 1985, Towne and Paramount were also dissatisfied with Evans’ performance and, after difficult deliberations, Evans was fired four days before production was scheduled to begin.

On top of existing problems in pre-production, including grievances filed by 120 crew members who had not been paid, over $500,000 in back salary claims from Screen Actor Guild (SAG) and Directors Guild of America (DGA) members, and $1.5 million of debt to suppliers of sets, props, costumes and sound stages who were also filing lawsuits, Nicholson refused to continue if Evans was dismissed, and the project was postponed indefinitely. Paramount, whose loss on the film totaled $4 million, claimed it had no legal obligation to crew members but paid over $200,000 to the California Division of Labor and Standards to settle their claims. In May 1985, a million dollars of sets, including Gittes’ office and the Morning Glory Bar and Grill, were dismantled and disposed of in their final stages of construction.

Despite cessation of production, various efforts were made to keep the project alive. Although Paramount owned the sequel rights to CHINATOWN, other major studios, including 20th Century Fox and MGM/UA, were reportedly vying to buy the project. In May 1986, The Cannon Group initiated negotiations to acquire the film, however, Evans was uncooperative about selling his stake in the project and losing his credit as producer. Although The Cannon Group was willing to give Evans credit as line-producer, Evans refused to accept this role and would not agree to the deal unless he had “full control.”

Meanwhile Nicholson’s career prospered with critically acclaimed roles in PRIZZI’S HONOR (1985) and HEARTBURN (1986). Nicholson’s involvement in HEARTBURN was elemental to the resurrection of THE TWO JAKES. Production on HEARTBURN was suspended when actor Mandy Patinkin was let go. Nicholson consented to a request from Paramount head Frank Mancuso, Sr. to step into the lead role with only three days’ notice. Mancuso was indebted to Nicholson, and wanted Paramount to maintain control over THE TWO JAKES, so negotiations between Nicholson and Mancuso in September 1988 resulted in reviving the project with Nicholson as director. In addition to Nicholson starring as “Jake Gittes,” actors Joe Mantell, Perry Lopez, and James Hong reprised their roles from CHINATOWN. Harvey Keitel was assigned the role of “Jake Berman.”

Towne sold the rights to his script to Paramount for approximately $1.5 million and points, but retained his role as writer. Nicholson insisted on significant rewrites to Towne’s script, which he found convoluted, and held out on signing his own contract with Paramount until Towne delivered an acceptable revision. Evans’ credit as producer was also preserved, although Paramount, not T.E.N. Productions, had authority over all finances and distribution rights. Producer Harold Schneider, who had previously worked with Nicholson, was hired to keep the budget under control and monitor the production on-set, as Evans’ direct involvement was reportedly waning.

Shooting began on 18 April 1989 in Los Angeles. Locations included Hollywood’s Max Factor Building and Dresden Restaurant, a nursery in Malibu, and Nicholson’s own residence. Principal photography wrapped 26 July 1989 at Nicholson’s home. A November 1989 Variety report describes several delays in releasing the film, making it ineligible for Academy Award consideration in 1989. Speculation that the delays reflected conflicts between Evans, Schneider and Paramount, and that the 144-minute running time of Nicholson’s cut of the film was problematic for studio executives, were denied by representatives from all parties.

Despite fairly positive reviews from the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times on 10 August 1990, THE TWO JAKES was not a box-office success and grossed under $10 million. Various reviews criticized the density and slow pace of Towne’s script. Nicholson’s voiceover narration throughout the film, which was added to the script by Nicholson during production despite objections from Towne, helped to clarify the plot.

Van Dyke Parks’ score was released by him as a composer promo. Its only commercial release has come on a CD from L.A. Music Enterprises in Australia. Although a third film had been intended to complete a Los Angeles trilogy, the critical and box office failure of THE TWO JAKES effectively killed the final project.

On 24 June 1990, the Los Angeles Times reported that writer Ira Levin was preparing for the March 1991 publication of SLIVER, his first novel since The Boys From Brazil (1976). Levin’s agent indicated that they would wait for reviews and sales figures before seeking a deal for film rights. A year later, producer Robert Evans had returned to Paramount Pictures, under a new five-year exclusive contract, after an eight-year hiatus from the studio as an independent producer. Ira Levin was reluctant to sell the rights to his book to anyone. He had only been pleased with the movie adaptation of ROSEMARY’S BABY (1968) out of all the attempts to film his novels. When Evans, who had produced ROSEMARY’S BABY, got wind of this, he sent Levin a copy of Roman Polanski's autobiography, with all the mentions of Evans' salvaging the film highlighted. The ploy worked and Levin sold the rights to Evans for $250,000.

Joe Eszterhas was selected to write the screenplay, and the budget was estimated at $30--$40 million. Robert Evans initially wanted Roman Polanski to direct the film. Since Polanski would not return to the United States, Evans planned on having a second unit director shoot some footage in New York, while Polanski would direct the film in Paris. Paramount didn’t like this idea, and approached director Stephen Frears, but ultimately hired Phillip Noyce, who had recently directed PATRIOT GAMES (1992) for the studio. Filming took place in Manhattan and the Los Angeles area.

Actresses considered for the role of “Carly Norris” included Michelle Pfeiffer, Julia Roberts, Meryl Streep, and Sharon Stone, star of Eszterhas’ BASIC INSTINCT (1992). Stone did not officially commit until shortly before the start of production, when Evans "bluffed" by claiming that actress Geena Davis, who was in competition with Stone for BASIC INSTINCT, had agreed to take the role. Despite hesitation from Paramount executives, the other principals--Noyce, Evans, Stone, and Eszterhas--insisted that William Baldwin read for the role of “Zeke Hawkins.”

In the film, Sharon Stone stars as a lonely book editor who moves into a swanky apartment building. William Baldwin owns the building and has high-tech video surveillance equipment installed everywhere so he can watch the tenants’ every move.

Although the 1993 thriller underperformed at the U.S. box office, grossing only $36 million, its $80 million take overseas turned it into a tidy profit-maker. None of Howard Shore's score appeared on the Virgin Records soundtrack CD.

In the 1995 thriller JADE, a bright assistant D.A. (David Caruso) investigates a gruesome hatchet murder and hides a clue he found at the crime scene because it points to the woman he still loves (Linda Fiorentino).

Producer Robert Evans again hired Joe Eszterhas (SLIVER) to write the script. But Eszterhas hated the final film. Director William Friedkin changed Eszterhas's script so much, Eszterhas threatened to remove his name from the credits. Paramount settled with him by giving him a "blind script deal" worth two to four million dollars. Later, Friedkin admitted that he did virtually rewrite the script, but Friedkin also said that this film was his favorite film he had ever made.

JADE was not a success, grossing only $9.8 million at the domestic box office. James Horner’s score was released by La-La Land in 2010.

Robert Evans and Alan Ladd, Jr. co-produced the 1996 action-adventure THE PHANTOM, based upon the comic strip of the same name. In the film, The Phantom (Billy Zane), descendent of a line of African superheroes, travels to New York City to thwart a wealthy criminal genius (Treat Williams) from obtaining three magic skulls that would give him the secret to ultimate power.

Simon Wincer directed the film. David Newman’s score was released by Milan. La-La Land released an expanded edition in 2012. THE PHANTOM was a box office disappointment, grossing just $17.3 million domestically.

Robert Evans was one of a quartet of producers for 1997’s THE SAINT. Based on a series of novels by Leslie Charteris, which also inspired the George Sanders' movies of the 1930s and '40s and the Roger Moore TV series of the '60s, THE SAINT places “Simon Templar” (Val Kilmer) in contemporary Russia, where a billionaire industrialist, played by Croatian actor Rade Serbedzija, is plotting to overthrow the democratic government and crown himself the first post-Soviet czar. Phillip Noyce (SLIVER) directed the film.

Paramount had been attempting to make a film of The Saint for more than 5 years. On May 29, 1991, Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat wrote that Finnish director Renny Harlin had signed a contract with Paramount to direct a new movie adaptation of The Saint, with Robert Evans producing. After this deal fell through, Paramount tried again with Evans, Steven Zaillian as writer, and Sydney Pollack as director. Ralph Fiennes was offered one million dollars for the lead, but eventually passed. In a 1994 interview for Premiere magazine, Fiennes said the screenplay--racing fast cars, breaking into Swiss banks--was nothing he hadn't seen before.

Robert Evans and Michelle Boyle at an event for THE SAINT

Graeme Revell’s score was released by Angel Records, while Virgin released the film’s songs. The film did well at the box office, grossing $61 million in the U.S. and another $57 million overseas.

Robert Evans was again one-fourth of the producing cadre for THE OUT-OF-TOWNERS, a 1999 remake of the 1970 film, which was based upon an original Neil Simon screenplay (here adapted by Marc Lawrence). The original film was one of the pictures that Evans had overseen during his first stint as head of production at Paramount during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The new film follows the adventures of a couple, “Henry” (Steve Martin) and “Nancy Clark” (Goldie Hawn), vexed by misfortune while in New York City for a job interview.

Sam Weisman directed the comedy. Marc Shaiman’s score was released by Milan. THE OUT-OF-TOWNERS did middling business at the U.S. box office, with a $28.5 million gross.

Robert Evans’ autobiography, THE KID STAYS IN THE PICTURE was published in 1994. A documentary of Evan’s life, based upon the book and co-written by Evans, was produced in 2002. The film’s narration, in which Evans portrays all the other characters as well as himself, is taken directly from the recording of the audio-book version of his autobiography. Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgen directed the film.

The title comes from a line attributed to studio head Darryl F. Zanuck. Several of the actors involved in the film THE SUN ALSO RISES (1957) (as well as author Ernest Hemingway himself) had insisted Evans be removed from the cast. Zanuck refused: "The kid stays in the picture! And anyone who doesn't like it can quit!"

Robert Evans and Leslie Ann Woodward at an event for THE KID STAYS IN THE PICTURE

Jeff Danna’s score shared space on the Milan soundtrack CD with various songs. For a documentary, the film did decent business, with a $1.5 million gross.

Along with Lynda Obst and Christine Peters, Robert Evans co-produced the 2003 romantic comedy HOW TO LOSE A GUY IN 10 DAYS. In the film, “Benjamin Barry” (Matthew McConaughey) is an advertising executive and ladies' man who, to win a big campaign, bets that he can make a woman fall in love with him in 10 days. “Andie Anderson” (Kate Hudson) covers the "How To" beat for Composure magazine and is assigned to write an article on "How to Lose a Guy in 10 days." They meet in a bar shortly after the bet is made.

Robert Evans at an event for HOW TO LOSE A GUY IN 10 DAYS

Donald Petrie directed the film. None of David Newman’s score appeared on the Virgin Records song-track CD. The film was a smash hit, bringing in $106 million domestically and another $71 million from foreign markets. It was the last theatrical feature produced by Robert Evans.

“Kid Notorious” was an adult animated television series that was a parody of Hollywood from the mind and mouth of Robert Evans. Evans was the co-creator, co-executive producer, and voiced the title character. Episode plots were often bizarre and absurdist in nature, featuring Evans as a James Bond type character. Guns N' Roses guitarist Slash also appeared on the show as himself, and Jeannie Elias voiced the character “Sharon Stone.” Directed by Pete Michels, the show aired from October 22 to December 17, 2003 on Comedy Central. It was cancelled after 8 episodes.

THE GIRL FROM NAGASAKI is a reworking of "Madame Butterfly," the Puccini opera about a 1904 U.S. Naval officer named Pinkerton (Edoardo Ponti) who rents a house on a hill in Nagasaki, Japan, for him and his soon-to-be wife, "Butterfly" (Mariko Wordell). This 2013 film recasts the story -- still set in Nagasaki -- in late 1950s Japan, with the title character a survivor of the atomic blast that leveled the city shortly before Japan surrendered to end WWII. Michael Nyqvist played "Father Lars." And Robert Evans returned to acting playing the U.S. Consul. The film played the Sundance Film festival, but did not get a theatrical release.

Mariko Wordell, Robert Evans, and director Michel Comte on the set of THE GIRL FROM NAGASAKI

Robert Evans retired from film work in 2013, except for co-executive producing a 2016 pilot for an “Urban Cowboy” television series that was not picked up. Evans was the inspiration for the “Stanley Motss” character played by Dustin Hoffman in WAG THE DOG (1997). Hoffman emulated Evans' work habits, mannerisms, quirks, his clothing style, hairstyle, and wore large square-framed eyeglasses. After seeing the picture, Evans reportedly said, "I'm magnificent in this film!"

According to his book Evans was contacted by Sharon Tate and asked to be her houseguest on the evening she was killed, but he had to decline. She then invited Jay Sebring.

In May 2002 Evans was awarded a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for Motion Pictures at 6925 Hollywood Blvd.

Looking back on his start as a producer, Evans remarked: “When I went out to L.A., I knew one thing: a property is king. No one wanted me--there's nothing worse than a pretty boy actor who wants to be a producer, especially a lousy actor. And I bought a property called THE DETECTIVE to get my foot in the door. So I went to 20th Century-Fox and demanded a three-picture deal and got it. Without the property, they wouldn't have given me anything.”

“The producer is the most important element of a film. It's the producer who hires the director. When a director hires a producer, you're in deep shit. A director needs a boss, not a yes man.”

“The producer buys the property, he hires the writer, the director; he's involved in hiring all the actors, involved with production, costs, post-production and involved with marketing. He's on a film for four or five years and gets very little credit for it.”

Thanks Robert, for producing some films we never tire of watching.

Robert Evans and John Wayne on the set of TRUE GRIT

Ali MacGraw, Robert Evans and Henry Kissinger

Ali MacGraw and Robert Evans, circa 1990

B.D.